SEVEN

FIREFIGHTS IN VIETNAM IA DRANG CONVOY AMBUSH PHUOC AN DAK TO LANG VEI US ARMY

US NAVY USMC

SOFTBOUND BOOK IN ENGLISH by

JOHN A. CASH, JOHN ALBRIGHT and ALLAN W. SANDSTRUM

FIGHT AT IA DRANG 14-16 NOVEMBER

1965 �WE WERE SOLDIERS ONCE�: the first major battle between the United States

Army and the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), as part of the Pleiku Campaign

conducted early in the Vietnam War, at the eastern foot of the Chu Pong Massif

in the central highlands of Vietnam, in 1965. It is notable for being the first

large scale helicopter air assault and also the first use of Boeing B-52

Stratofortress strategic bombers in a tactical support role. Ia Drang set the

blueprint for the Vietnam War with the Americans relying on air mobility, artillery

fire and close air support, while the PAVN neutralized that firepower by

quickly engaging American forces at very close range. Ia Drang comprised two

main engagements, centered on two helicopter landing zones (LZs), the first

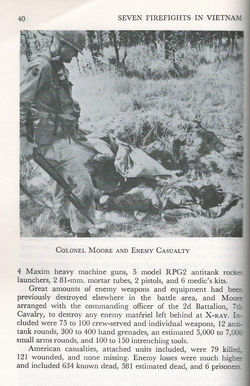

known as LZ X-Ray, followed by LZ Albany, farther north in the Ia Drang Valley. LZ X-Ray involved the 1st Battalion, 7th

Cavalry Regiment and supporting units under the command of Lieutenant Colonel

Hal Moore, and took place November 14�16, at LZ X-Ray. Surrounded and under

heavy fire from a numerically superior force, the American forces were able to

drive back the North Vietnamese forces over three days, largely through the

support of air power and heavy artillery bombardment, which the North

Vietnamese lacked. The Americans claimed LZ X-Ray as a tactical victory, citing

a 10:1 kill ratio.

CONVOY AMBUSH ON HIGHWAY 1, 21

NOVEMBER 1966: When the 11th Armored Cavalry-the "Blackhorse

Regiment"- arrived in the Republic

of Vietnam in September 1966, the threat of ambush hung over every highway in the country. Since the

regiment's three squadrons each had a

company of main battle tanks, three armored cavalry troops, and a howitzer battery, the Blackhorse was well suited for

meeting the challenge. Each of the

cavalry troop's three platoons had nine armored cavalry assault vehicles (ACAV's). The ACAV was an M113

armored personnel carrier modified for

service in Vietnam and particularly adapted to convoy escort. With the M113's usual complement of one .50-caliber

machine gun augmented by two M60 machine

guns, all protected by armored gun shields, and with one of its five-man crew armed with a 40-mm. grenade launcher,

the vehicle took on some of the

characteristics of a light tank. Fast, the track-laying ACAV could keep

pace with wheeled vehicles and also

deliver withering fire. Aware that

convoy escort would be a primary mission of the 11th Cavalry, the regiment's

leaders had concentrated in the five months between alert and departure for

Vietnam on practicing counter ambush techniques. In countless mock ambushes,

the cavalrymen learned to react swiftly with fire. The first object was to run

thin-skinned vehicles out of the killing zone; the armored escorts would then

return to roll up the enemy's flanks, blasting with every weapon and crushing

the enemy beneath their tracks. In

mid-October, a month after arriving at a staging area at Long Binh, a few kilometers northeast of Saigon, the

regiment issued its first major operational

order. The Blackhorse was to establish a regimental base camp on more

than a square mile of ground along Interprovincial Highway 2, twelve

kilometers south of the provincial

capital of Xuan Loc.

AMBUSH AT PHUOC AN 18 JUNE 1967:

Before the mid- 1965 build-up of American troops in the Vietnam War, it could

be said with some degree of certainty that "the night belongs to the Viet

Cong." But as the American offensive operations mounted, the enemy could

no longer use darkness with impunity. On

any given night in Vietnam, American soldiers staged hundreds of ambushes, for

the ambush is one of the oldest and most effective military means of hampering

the enemy's nighttime exploits. Sometimes an ambush was used to provide

security for a defensive position or a base camp, sometimes simply to gain

information, and at other times to protect villages against enemy terrorists.

During the night of 18 June 1967, ten infantrymen of the U.S. 196th Light

Infantry Brigade set an ambush at a point sixteen kilometers south of Chu Lai,

in Quang Ngai Province, in the hope of waylaying enemy terrorists. As part of

Task Force OREGON, the brigade had been conducting offensive operations to

assure the security of the Chu Lai base complex. To this end, the 3d Battalion,

21st infantry, was sending out patrols from a battalion base of operations ten

kilometers south of Chu Lai and just north of the Song Tra Bong River, with the

specific mission during daylight hours of looking for possible mortar or rocket

sites that might pose a threat to the Chu Lai airstrip and at night of

establishing ambushes near locations of suspected enemy activity. To accomplish

its mission, the ad Battalion had divided its area of responsibility into

company sectors, assigning to Company A a sector that included two hamlets,

Phuoc An (1) and Phuoc An (2). When a week's search had uncovered no mortar or

rocket sites, the Company A commander decided to establish an ambush in the

vicinity of the two hamlets. One of his patrols had heard screams and unusual

commotion from one of the hamlets and, later, intelligence reports had

indicated that aggressive patrolling just might turn up

FIGHT ALONG THE RACH BA RAI

RIVER, 15 SEPTEMBER 1967: The murmur of voices and the scrape of weapons

against the sides of the steel ship penetrated the damp night as the men of the

3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, climbed from a barracks ship, the USS Colleton,

and into waiting landing craft alongside. It was 0300, 15 September 1967.

Within minutes after boarding the boats, most men slept. Late the previous day

they had come back from a three-day operation during which, in one sharp,

daylong battle, nine of their comrades had fallen, along with sixty of the enemy.

There had been time during the night to clean weapons, shower, eat a hot meal,

and receive the new operations order, but not much time to sleep off the now

familiar weariness that engulfed these infantrymen after days of fighting both

the Viet Cong and the mud of the Mekong Delta.

Three days before Col. Bert A. David's Mobile Riverine Brigade, the 2d

Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division, and its Navy counterpart, Task Force 117,

had set out to search for and destroy the 514th Local Force and 263d Main Force

Viet Cong Battalions. When the enemy was finally found, the ensuing battle had

only weakened, not destroyed, the Viet Cong battalions, which broke off the

fight and slipped away. Thus, when

intelligence reports that reached the Riverine Brigade's headquarters on the

afternoon of 14 September placed the Viet Cong in the Cam Son Secret Zone along

the Rach Ba Rai River, Colonel David resolved to attack. (See Map 1) Quickly he

pulled his units back from the field and into their bases to prepare for a

jump-off the next morning. For the 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, that meant a

return to the USS Colleton, anchored in the wide Mekong River near the Mobile

Riverine Force's base camp at Dong Tam. The 263d Main Force Viet Cong Battalion

attacks a Mobile Riverine Force convoy on the Rach Ba Rai River, in the Mekong

Delta. The American force is comprised of a U.S. Army Mobile Riverine brigade

and elements of Navy Task Force 117. When the U.S. convoy rounds a bend in the

river, the Viet Cong attack with rockets, recoilless rifles, and small arms.

They hit 21 boats and kill 7 American servicemen while wounding 123 men. Many

of the casualties are Navy Sailors from Task Force 117, making it one of the Navy�s

costliest riverine actions to date. The majority of the Viet Cong battalion

slips away during the night, leaving behind 79 dead.

THREE COMPANIES AT DAK TO, 6

NOVEMBER 1967: In early February 1954, French Union forces were drawn into the

final, convulsive combat actions of the Indochina War. A closing act of that

drama took place on 2 February when the Viet Minh launched simultaneous attacks

in battalion strength that overwhelmed all French outposts northwest of Kontum

City. By 7 February the French high command, realizing that its tenuous hold on

Kontum Province had been broken, evacuated the provincial capital. The ejection

of French forces from this key province in the Central Highlands marked a giant

step in the march of Communist insurgency.

Thirteen years later, reconstituted Communist forces readied another

major effort in Kontum Province. Although the stage was the same, the cast and

scale of confrontation were somewhat different. This time regular units of the

North Vietnamese Army (NVA) prepared to strike a telling blow against South

Vietnamese and U.S. Military Assistance Command forces. The North Vietnamese

Army objective was not to reduce all Free World outposts in Kontum, but to

chalk up a sorely needed victory by seizing just one- the Dak To complex-a few

kilometers from a key French post of the same name that was overrun in 1954. Dak To was one of a chain of Civilian

Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) camps advised by U.S. Special Forces personnel.

Situated in the west central part of Kontum Province, it could be reached from

Pleiku City by following Route 14 north through Kontum City and then turning

west on Route 512. North of Dak To, Route 14 rapidly deteriorated as it

approached a CIDG camp at Dak Seang. Still farther to the north the road became

so poor that another camp at Dak Pek had to rely solely on an aerial life line.

BATTLE OF LANG VEI, 7 FEBRUARY

1968: The Battle of Lang Vei (Vietnamese: Trận L�ng V�y) began on the evening

of 6 February 1968 and concluded during the early hours of 7 February, in Quảng

Trị Province, South Vietnam. Towards the end of 1967, the 198th Tank Battalion

of the People's Army of Vietnam's (PAVN) 202nd Armored Regiment received

instructions from the North Vietnamese Ministry of Defense to reinforce the

304th Division as part of the Route 9�Khe Sanh Campaign. After an arduous

journey down the Ho Chi Minh trail in January 1968, the 198th Tank Battalion

linked up with the 304th Division for an offensive along Highway 9, which

stretched from the Laotian border through to Quảng Trị Province. On 23 January,

the 24th Regiment attacked the small Laotian outpost at Bane Houei Sane, under

the control of the Royal Laos Army BV-33 "Elephant" Battalion. In

that battle, the 198th Tank Battalion failed to reach the battle on time because

its crews struggled to navigate their tanks through the rough local terrain.

However, as soon as the PT-76 tanks of the 198th Tank Battalion turned up at

Bane Houei Sane, the Laotian soldiers and their families retreated into South

Vietnam. After Bane Houei Sane was

captured, the 24th Regiment prepared for another attack which targeted the U.S.

Special Forces Camp at Lang Vei, manned by Detachment A-101 of the 5th Special

Forces Group and indigenous Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) forces. On

6 February, the 24th Regiment, again supported by the 198th Tank Battalion,

launched their assault on Lang Vei. Despite artillery and air support, the

U.S.-led forces conceded ground and the PAVN quickly dominated their positions.

By the early hours of 7 February the command bunker was the only position still

held by Allied forces. To rescue the American survivors inside the Lang Vei

Camp, a counterattack was mounted, but the Laotian soldiers who formed the bulk

of the attack formation refused to fight the PAVN. Later on, U.S. Special

Forces personnel were able to escape from the camp and were rescued by a U.S.

Marine task force from Khe Sanh Combat Base.

GUNSHIP MISSION, 5 MAY 1968: By

mid-1966 gun helicopter platoons, each platoon consisting of eight UH-1 (Huey)

helicopters armed with rockets and machine guns and each platoon organic to an

assault helicopter company, were hard at work all over South Vietnam. Usually

five of the Hueys in a platoon were kept ready at all times while the other

three were held in reserve or were undergoing maintenance. Four of the ready

gunships flew in pairs, designated light fire teams. The fifth could be used to

augment the fire of either team, and when so employed the three ships

constituted a heavy fire team. Operating in support of American, South

Vietnamese, and allied forces, these fire teams had a hazardous assignment, for

the relatively slow-moving helicopter, flying at low levels, is highly vulnerable

to ground fire. So valuable was the ships' support to ground troops, however,

that the risks were considered justifiable. In the spring of 1968 an incident

occurred on the outskirts of Saigon, the South Vietnamese capital, that

illustrates some of the methods used by the fire teams. The strong offensive launched by the North

Vietnamese and the Viet Cong during the Tet holiday had ended, but intelligence

sources indicated the possibility of a follow-up assault against the capital.

During late April and the first few days of May, substantial enemy forces were

reported moving closer to Saigon from three directions. To meet the enemy threat, Maj. Gen. Le Nguyen

Khang, the South Vietnamese Army commander responsible for the defense of the

city, relocated his forces, which normally operated in the outlying areas

surrounding Saigon, to form a defensive ring closer to the city. As a part of

the new deployment, he installed the three battalions of the South Vietnamese

5th Ranger Group on the edge of the Cholon sector in southwestern Saigon.

General Khang charged his units with locating enemy caches, preventing

infiltration of men, weapons, ammunition, and equipment, and destroying any

enemy forces that might manage to slip in.

The 5th Ranger Group, to carry out this order, placed two companies of

its 30th Ranger Battalion in approximately thirty ambush positions along a

north-south line a few kilometers west of the Phu Tho Racetrack, in the center

of the Cholon sector, with another company behind them as a blocking force. A

fourth company continued to perform security duties at the battalion base camp,

eight kilometers away. In addition to

reinforcements available from II Field Force and Vietnamese III Corps

headquarters and on-call artillery arid air strikes, General Khang's units

could ask for assistance from the gunships of the 120th Aviation Company

(Airmobile, Light). At that point in the Vietnam fighting, the 120th Aviation

Company was not engaged in the combat assaults usually performed by such units

but was assigned to provide administrative transportation for headquarters of

the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), and headquarters of the United

States Army, Vietnam (USARV). In April 1968, however, MACV headquarters had

directed that four armed helicopters of the company's gunship platoon be made

available to Capital Military District headquarters to provide fire support for

ground troops in and around Saigon. One fire team was to be on 5-minute alert

status on the Air Force flight line at Tan Son Nhut Air Base while the other

was to be on 30-minute standby at the gunship platoon headquarters on the Tan

Son Nhut Air Base helipad. These gunships of the 120th Aviation Company were

later to become heavily involved in the defense of Saigon against a major enemy

attack. Before dawn on 5 May 1968 the

enemy offensive erupted. A battalion of a main force Viet Cong regiment with an

estimated strength of 300 men attacked the Newport Bridge and adjacent docking

facilities along the waterfront in northeastern Saigon. The fight was joined.