GORGO After a seaquake, a huge lizard-like creature walked out of the ocean and almost destroyed a fishing village in Ireland. Fortunately for the village, the same quake that brought the 65 foot monster to land has also grounded a salvage ship, the crew of which proved up to the task of capturing the beast. Instead of killing it, or turning it over to the government, they decided to take it to London and put it on display for profit. Looking to be a huge success, things became more complicated when it was discovered the monster, dubbed Gorgo, was really just a youngster and it’s 200 foot tall mother was coming for him. After a pitched battle with the British army, Gorga’s mother, Ogra, was able to free her child and they both went lumbering back to the sea. That, however, was not the last the world heard of Gorgo. Apparently having found a taste for the land, the young monster began to make regular visits there. At the same time, governments, scientists, and even would-be world conquerors pursued Gorgo and his mother for their own ends. In regards to humanity, Gorgo would show a curiosity towards them and even befriend some individuals to the point of letting them ride on his head. If he was attacked, however, Gorgo would hunt down those who had hurt him. This led Gorgo to finding himself in a succession of dangerous situations, from battling other giant primitive monsters, to control by mad scientists, to even at one point inadvertently preventing World War III and landing on the Moon.

In theory, the 1961 giant monster movie Gorgo should've had a lot going for it. It was the brainchild of creator and director Eugène Lourié, who in 1953 had pioneered the 1950s-era monster movie trend with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Based on a Ray Bradbury short, the Beast was an atomic radiation-created giant monster film that directly inspired Godzilla the next year. Lourié would go onto become a critically acclaimed director, production designer, and art director, and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects on the 1959 film Krakatoa, East of Java.

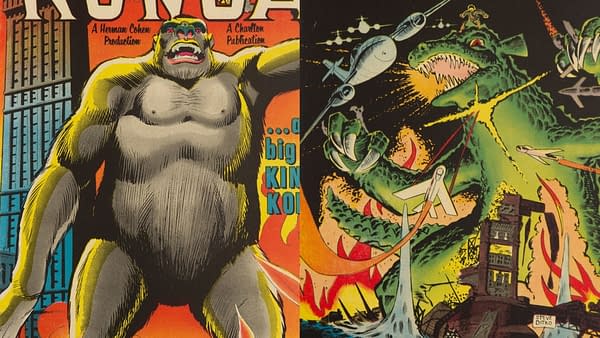

Konga (1960) and Gorgo (1961), Charlton Comics.

Konga (1960) and Gorgo (1961), Charlton Comics.Meanwhile, successful B-movie producer Herman Cohen, fresh off the surprise success of his I Was a Teenage Werewolf (and its follow-up I Was a Teenage Frankenstein) had been looking for another follow-up. He settled on Konga, sort of a color version of King Kong. Perhaps Cohen should've stuck with his working title, I Was a Teenage Gorilla, because Konga was underwhelming and poorly received. As for Gorgo, the film made Lourié swear off the giant monster genre that he had helped pioneer. And somehow, both Gorgo and Konga are best remembered by fans today because legendary comics creator Steve Ditko worked on the comic book versions of both of them.

The licensed Charlton Comics versions of both these films, both initially created by Joe Gill and Steve Ditko, manage to transcend their film screenplay inspirations. According to the book Ditko Monsters Konga and Gorgo from Yoe Books, Ditko would say of Gill's work on Gorgo, "I read the screenplay of Gorgo. From the first reading to this day, I marvel at how well Joe adapted the character to comic books."

Charlton Comics was founded in 1946 and went out of business in 1985. The company published comic books in a wide range of genres, reflecting whatever were the variety of popular trends at a given time, much the same way Timely/Atlas did. Charlton published War Comics, Horror Comics, Cartoon Comics, Teen comics, Humor Comics, Superhero Comics, Kung Fu Comics, Action Adventure Comics, Romantic Comics and Science Fiction Comics. The wider publishing company published song-lyric magazines (popular in the 1940's), puzzle magazines (of the type often found at supermarket check out lines), Digest-sized story magazines, and paperbacks under the imprints Monarch and Gold Star.

Charlton began as a magazine printing concern, Charlton Publications, of which comic books were only one small facet. Begun in 1940 under founders John Santangelo, Sr. & Edward Levy, the company was originally called T.W.O. Charles Company, named for the two sons of the co-founders, both of whom were named Charles. The company renamed itself Charlton Publications in 1945. In its early years the company's lead editor was Al Fago, brother to Timely comics' lead funny animal artist, Vince Fago.

Charlton was a unique company in that unlike larger publishing concerns, Charlton's entire production process for its comic books (as well as its other published output) was entirely produced under its own auspices; every phase of production, from Editorial art creation to Printing to Distribution, came directly from the company's editorial headquarters/printing plant in Derby Connecticut. (in fact, that alone would make Charlton unique as a publisher. Photos exist of the offices of "Charlton Publications" which feature a massive building -- the printing plant--looking more like the factory it in fact was than a publishing concern)

While in one way this unique organizational structure gave the company singular control of its product, it also meant that if the company didn't particularly care about the quality of its output, it had to answer to no one (except of course it readers. More on that in a moment). Since the comic-book line was essentially created as a way to keep the company's massive printing facility up and running overnights, (since shutting down the gigantic industrial printers for the night and then starting them up again in the morning would be prohibitively expensive) they were decidedly less critical about the quality exhibited in their comics. Charlton was notorious for the low quality control they exerted over the comics they produced--the quality of their comic-book paper was often a much cheaper grade than higher-end publishers, there was less oversight of the registration of printing plates, so no matter the quality of the artwork, patches of color often floated far and wide from the lines that were meant to border them, and of course because they paid so little, their artists were often less careful about the quality of their artwork or so overworked (adding page count as a way to fill up a decent paycheck) that their books' artwork suffered in comparison to other publishers--- as well as for the extremely low page rates they paid to their artists and writers. At the same time, the company often exerted less stringent editorial control over their comics, which could meant that their artists could exhibit a distinctively expressive personal style even at a time when "house styles" were dominant in the comics industry.

The company's fortunes ebbed and grew across the decades, often dependent on how other larger comics concerns were doing. For example, as the comics boom ebbed after WWII, so did Charlton. As the boom in horror comics in the 50's grew the industry overall, so grew Charlton, if on a smaller scale. Its lead horror title, The Thing! featured seminal early work by the young Steve Ditko in what was at the time one of the most garish and violent horror comics of the era. Charlton's knack for imitation is most evident in the wake of the 1960's Marvel Age of Comics," when Ditko left Marvel and lent his talents to Charlton -- precisely BECAUSE of Charlton's lesser editorial control over his work-- and the quality of Charlton's product went up commensurately. The same minor revival happened in the mid-70's, with an influx of fresh new talent to the industry, who could find a welcome work opportunity (and that lower paycheck) at Charlton, always hungry for new talent to exploit. Soon-to-be-stellar artists like Dick Giordano, who later became editor-in-chief at the company before moving to fame and fortune (and a renowned collaborative partnership with Neal Adams) at DC, Jim Aparo, Frank McLaughlin and others in the 60's, and John Byrne, Joe Staton, Wayne Howard, and others in the 1970's got their starts at the Derby, CT based funnybook company.

As editor, Giordano in the 1960's spearheaded the company's push into the Superhero genre (Giordano preferring to call them "Action Heroes") in the company's effort to follow the burgeoning trend in the market. They grew their line, and with the disaffected Ditko at the high end of their creative roster the company made their feeble push into market expansion. While fondly remembered by fans, it remained that the quality of Charlton's product really did pale in comparison to the larger concerns like Marvel & DC, and the sales numbers reflected the tastes of the buying public.

"Aw heck, sold out of Spider-Man?" some gum-chewing moppet would cuss at the newsstand spinner rack, "I'll have to settle for this lousy Blue Beetle..."

Notably, however, Charlton's loose editorial oversight permitted craftsmen like Ditko and his collaborator Joe Gill to give vent to some of the most extreme Ayn Randian libertarian politics ever exhibited in comics, in text heavy dialog balloons spouted by characters such as The Blue Beetle and especially The Question, a character created specifically to embody those political views, and a precursor to Ditko's own later character Mr. A. The Question spent most of his career as a backup feature to The Blue Beetle, but did warrant an over-long special issue devoted exclusively to the character, Mysterious Suspense #1, published in 1968 with a 25-page Question story made up of what appears to be shorter pieces intended for backups in the cancelled Blue Beetle title, collected into the longer story for this one-off issue.

Critical appraisal of most of Charlton's output would rate most of what they produced poorly versus the larger competition, though some genres were superior to others. The superhero books were a pale comparison to the likes of Marvel & DC, but their feeble horror and ghost titles managed to be moody and often downright weirder than their competitors comic-code neutered products. Charlton was a large licensor of characters from other media -- cartoon characters from television and motion pictures, (even oddballs like Hong Kong Phooey) and comic strip characters such as The Phantom-- and those titles were often a steady stream of income for the company when their attempts at superheroes bombed after a few issues. Some in fandom actually rate Charlton's Romance comics -- a genre objectively at best a feeble, pallid imitation of real-life at best from almost any company except the likes of St. John in the 50's-- on a par with any of its competitors, even with its rotten printing, off-register colors and coarse, cheap paper.

Romance comic books were one place where Charlton was able to exhibit some distinction, the comic-book slum of that genre which attracted primarily young female readers and which no boy would admit to reading (but given that the females were well-rendered, drawn primarily by men as unrealistically well-endowed, and often exhibited in passionate embrace with their paramours, almost all male readers did at one time or another, if only to later cast it off after getting the pages stuck together). Larger companies like Atlas and DC produced some distinctive and notable romance titles for some time in the 1950's, 60's and 70's. Some smaller companies like St. John produced romance books that were uniformly excellent (or at least of passable readability, given comics' inability to deal at the time with anything approaching an adult theme. St John at least tried) Charlton was in no place to compete on quality, given its low production values, so they competed by turning out a dizzying volume of romance titles from the late 50's through the early 80's. The company hit its peak from about 1958 to 1966, with just some titles during this period being: Brides in Love, Cowboy Love, First Kiss, I Love You, Intimate, Just Married, Love Diary, My Secret Life, Negro Romances, Pictorial Love Story, Romantic Secrets, Romantic Story, Secrets of Love & Marriage, Secrets of Young Brides, Sweethearts, Sweetheart Diary, Teen-Age Love, Teen Confessions, and Teen-Age Confidential Confessions. This incomplete list nevertheless is exemplary of a practice used on the company's entire line, and an approach to comic book making: most of these titles were purchased from bankrupt competitor companies, many rehashed the same stories again and again, and examples exist documenting Charlton's note-for-note plagiarizing stories and swiping poses for those stories form other companies. And while the comics code imposed a sterility on these comics that a superior producer like St. John did not have to deal with, these books' art almost makes up for the tired soap opera of the narratives.

(This practice, of building a stable of titles by purchasing properties from other companies on the verge of insolvency, included characters such as The Blue Beetle, purchased from Fox Publications, and several horror & crime titles from defunct publishers such as Fox Comics, Canadian publisher Superior Comics, Mainline, the previously mentioned St. John and the comic-book division of Fawcett Publications when that company lost a prolonged legal battle with DC over the alleged copyright infringement of Fawcett's Captain Marvel upon DCs Superman.)

While it is true that readers of romance comics claim that DC's art was superior to that of Charlton, such is a matter of personal opinion. The author of this paragraph and apparently an extreme fan of romance comic art in general is of the view that from the late 1950's to the mid 1960's, Charlton's romance titles were just as good as those from DC and probably a shade better. At the very least, the artwork, by the likes of Vince Colletta, Nicholas Alascia, Jon D'Agostino, Sal Trapani, Charles Nicholas and others, could stand against the rest of the romance books on the rack, even if Charlton's were more cheaply produced. Colletta in particular excelled at implying a subtle eroticism to his figurative posing in a manner that meant that Charlton could count on the appeal of some of these titles, as mentioned earlier, to easily excite adolescent boys as well as the books' intended audience of young girls (who were simultaneously being drilled on culturally acceptable gender roles at the same time).