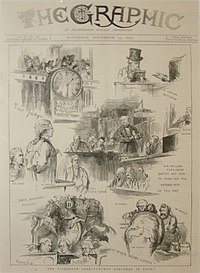

The Graphic was a British weekly illustrated newspaper, first published on 4 December 1869 by William Luson Thomas's company Illustrated Newspapers Ltd. Thomas's brother Lewis Samuel Thomas was a co-founder. The premature death of the latter in 1872 "as one of the founders of this newspaper, [and who] took an active interest in its management" left a marked gap in the early history of the publication.[1] It was set up as a rival to the popular Illustrated London News.

The influence of The Graphic within the art world was immense, its many admirers included Vincent van Gogh, and Hubert von Herkomer.[2]

It continued to be published weekly under this title until 23 April 1932 and then changed title to The National Graphicbetween 28 April and 14 July 1932; it then ceased publication, after 3,266 issues. From 1890 until 1926, Luson Thomas's company, H. R. Baines & Co., published The Daily Graphic.

Background[edit]

The Graphic was founded by William Luson Thomas, a successful artist, wood-engraver and social reformer. Earlier he, his brother and his brother-in-law had been persuaded to go to New York and assist in launching two newspapers, Picture Gallery and Republic. Thomas also had an engraving establishment of his own and, aided by a large staff, illustrated and engraved numerous standard works.[3] Exasperated, even angered, by the unsympathetic treatment of artists by the world's most successful illustrated paper, The Illustrated London News, and having a good business sense Luson Thomas resolved to set up an opposition. His illustrated paper, despite being more expensive than its competition, became an immediate success.[2]

Realisation[edit]

When it began in 1869, the newspaper was printed in a rented house. By 1882, the company owned three buildings and twenty printing presses, and employed more than 1,000 people. The first editor was Henry Sutherland Edwards. A successful artist himself, the founder Thomas recruited gifted artists including Luke Fildes, Hubert von Herkomer, Frank Holl, and John Everett Millais.

The Graphic was published on a Saturday and its original cover price was sixpence, while the Illustrated London News was fivepence.[2] In its first year, it described itself to advertisers as "a superior illustrated weekly newspaper, containing twenty-four pages imperial folio, printed on fine toned paper of beautiful quality, made expressly for the purpose and admirably adapted for the display of engravings".

In addition to its home market the paper had subscribers all around the British Empire and North America. The Graphic covered home news and news from around the Empire, and devoted much attention to literature, arts, sciences, the fashionable world, sport, music and opera. Royal occasions and national celebrations and ceremonials were also given prominent coverage.

Artists[edit]

Artists employed on The Graphic and The Daily Graphic at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century included Helen Allingham, Edmund Blampied, Alexander Boyd, Frank Brangwyn, Randolph Caldecott, Lance Calkin Léon Daviel, John Charles Dollman, James H. Dowd, Godefroy Durand, Luke Fildes, Harry Furniss, John Percival Gülich, George du Maurier, Phil May, George Percy Jacomb-Hood, Ernest Prater, Leonard Raven-Hill, Sidney Sime, Snaffles (Charles Johnson Payne), George Stampa, Edmund Sullivan, Bert Thomas, F. H. Townsend, Harrison Weir, and Henry Woods.

The notable illustrator Henry William Brewer, contributed a regular illustrated article on architecture to the magazine for 25 years, until his death in 1903.[4][5]

Writers[edit]

Writers for the paper included George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, H. Rider Haggard and Anthony Trollope.[6] Malcolm Charles Salaman was employed there from 1890 to 1899. Beatrice Grimshaw travelled the South Pacific reporting on her experiences for the Daily Graphic.[7] Mary Frances Billington served the Graphic as a special correspondent from 1890 to 1897, reporting from India in essays that were compiled into Woman in India (1895).[8] Joseph Ashby-Sterry wrote the Bystander column for the paper for 18 years.

M. Duruof

The last balloon voyage of exceptional interest which our space will permit us to mention is that of M. Jules Duruof, whose stirring adventure between Paris and Tours we have already detailed. The ascent took place at Calais on the evening of August 31st, 1874, and the aeronaut was accompanied by his wife. It is no part of our duty to narrate the circumstances under which the ascent took place; suffice it to say that the intrepid aeronauts went up against their own will, and with a full conviction that it was almost certain death to do so. Their escape was marvellous. On ascending, they found the wind blowing in a north-easterly direction, and the balloon was driven across the sea towards England. As night approached, M. Duruof attempted to attract the attention of some of the vessels beneath him, but for some time without effect. At length they were descried by the crew of a fishing smack—the Grand Charter, of Grimsby. The story of the rescue cannot be told better than by M. Duruof himself:—" The sea was very rough indeed. I opened the valve and descended until the ropes were trailing in the water, and in an instant we were past the vessel. The crew of the smack, however, launched the boat, and two men rowed it towards us. It was then six o'clock, and seeing the good-will of the fishermen to come and help us, I resolved to stop the speed of the balloon by springing the valve until the car filled with water, and thus give more resistance to the progress of the balloon. However, when I turned round, I could not see the vessel. From time to time tremendous waves broke over the balloon, covering us with water; but still the balloon resisted, and my fear then was that the balloon might burst, in which case we should assuredly been lost. At seven o'clock we again sighted the smack on the horizon, and saw that she was pursuing us, and by degrees we noticed that she came closer to us. The cold was very severe, and our limbs were becoming benumbed. Our strength was failing us, and the hope of being overtaken by the smack was the only thing that gave strength to our arms to hold on by. My wife's limbs were benumbed, and at each jerk of the balloon she became weaker and weaker. The smack continued to approach us, and was now within 500 mètres. I pointed it out to my wife, and it renewed her courage. What was more tiring: was being obliged to hold her in my arms. The smack was then very near us, and I raised myself on the ropes and saluted our rescuers. They saw us and launched their boat, being 200 mètres ahead of us. The small boat was manned by the master (William Oxley) and the mate (James Bascombe). They came nearer to the car, and took hold of the rope. At this time their boat was nearly sinking, on account of the strong jerks of the balloon, but they did not lose courage, and taking hold of my wife's hand, who was like a corpse, dragged her as best they could into their boat. I saw the danger they were in, and I began to cut the ropes that were following the balloon. I had cut the greater part of them when I was dashed against the boat, and I let myself fall into it. I, like my wife, lay helpless in the bottom of the boat. The men let go the ropes of the car, and the balloon rushed off with a mighty speed towards Norway."

The daring aeronaut and his brave wife were conveyed to the smack by their gallant rescuers, and were landed safely at Grimsby. So little effect had their perilous adventure upon them, however, that M. Duruof made an ascent, at which his wife was also present, at the Crystal Palace on September 14th. The balloon was picked up a few days afterwards on the coast of Norway.

Serbian–Ottoman Wars (1876–1878)

| Serbian–Ottoman Wars (1876–1878) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Eastern Crisis | |||||||||

Battle of Moravac | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 130,000 with 160 guns[1] | 153,000 with 192 guns[1] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| First Serbian-Ottoman War: 6,000 killed, 9,500 wounded[2] Second Serbian-Ottoman War: 5,410 dead and wounded[1] (708 killed, 1,534 died, missing 159, wounded 2,999)[3] | First Serbian-Ottoman War: 1,000+ killed,[4] several thousand wounded[5] Second Serbian-Ottoman War: 1,750 taken prisoner[3] | ||||||||

The Serbian–Ottoman Wars (Serbian: Српско-османски ратови, romanized: Srpsko-osmanski ratovi), also known as the Serbian–Turkish Wars or Serbian Wars for Independence (Српски ратови за независност, Srpski ratovi za nezavisnost), were two consequent wars (1876–1877 and 1877–1878), fought between the Principality of Serbia and the Ottoman Empire. In conjunction with the Principality of Montenegro, Serbia declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 30 June 1876. By the intervention of major European powers, ceasefire was concluded in autumn, and the Constantinople Conference was organized. Peace was signed on 28 February 1877 on the basis of status quo ante bellum. After a brief period of formal peace, Serbia declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 11 December 1877. Renewed hostilities lasted until February 1878.

At the beginning of the conflict, the Serbian army was poorly trained and ill-equipped, unlike the troops of the Ottoman Empire. The offensive objectives the Serbian army sought to accomplish were overly ambitious for such a force, and they suffered a number of defeats that resulted from poor planning and chronically being spread too thin. This allowed Ottoman forces to repel the initial attacks of the Serbian army and drive them back. During the autumn of 1876, the Ottoman Empire continued their successful offensive which culminated in a victory on the heights above Đunis. During the second conflict, between 13 December 1877 and 5 February 1878, Serbian troops regrouped with help from Imperial Russia, who fought their own Russo-Turkish War. The Serbs formed five corps and attacked Ottoman troops to the south, taking the cities of Niš, Pirot, Leskovacand Vranje one after another. The war coincided with the Bulgarian uprising, the Montenegrin–Ottoman War and the Russo-Turkish War, which together are known as the Great Eastern Crisis of the Ottoman Empire.[6]