WELLINGTONS

MILITARY MACHINE HBDJ BRITISH ARMY ROYAL NAVY NAPOLEONIC WARS TRAFALGAR

WATERLOO HISTORY UNIFORMS WEAPONS

HARDBOUND BOOK with DUSTJACKET

in ENGLISH by PHILIP J. HAYTHORNTHWAITE

RECRUITMENT, TRAINING &

DRILLING

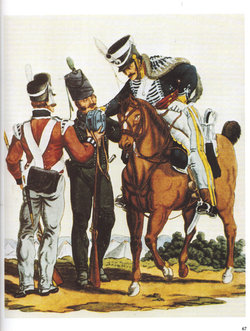

THE CAVALRY (1ST LIFE

GUARDS, HEAVY CAVALRY, 1ST ROYAL DRAGOONS, THE LIGHT DRAGOONS, THE

HUSSARS, THE YEOMANRY CAVALRY)

THE INFANTRY (23RD

ROYAL WELCH FUZILEERS, 6TH (1ST WARWICKSHIRE) REGT, THE

FOOT GUARDS, COLDSTREAM, SCOTS, THE LINE REGIMENTS, BROWN BESS INFANTRY MUSKET,

SHOULDER BELT BREASTPLATE, GRENARDIERS, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE, NORTHUMBERLAND, PRINCE

OF WALE’S VOLUNTEERS, THE SCOTTISH REGIMENTS, 92ND HIGHLANDERS, 79TH

HIGHLANDERS, 97TH HIGHLANDERS, BIG SAM MacDONALD, 71ST

GLASGOW HIGHLAND LIGHT INFANTRY, THE IRISH REGIMENTS, 87TH FOOT, 88TH

FOOT, THE LIGHT INFANTRY, THE RIFLE CORPS, MILITIA, FENCIBLES, VOLUNTEERS)

THE ARTILLERY (ROYAL FOOT

ARTILLERY, FIELD ARTILLERY, CONGREVE’S BLOCK TRAIL CARRIAGE, THE HORSE

ARTILLERY, SIEGE AND GARRISON ARTILLERY)

THE SUPPORTING ARMS SERVICES (THE

COMMISSARIAT, MEDICAL SERVICES, ROYAL NGINEERS, STAFF & INTELIGENCE)

BRITAIN’S ALLIES (THE KING’S

GERMAN LEGION, THE SPANISH, THE PORTUGUESE, THE HANOVERIANS, THE NETHERLANDERS

DUTCH, THE RUSSIANS, AUSTRIANS & SWEDES, THE PRUSSIANS, THE EMIGRANT CORPS,

THE FOREIGN CORPS)

STRATEGY AND TACTICS (WELLINGTON

ON THE PENINSULA, ON THE MARCH, THE LINE, THE SQUARE, LIGHT INFANTRY TACTICS,

ARTILLERY TACTICS, CAVALRY TACTICS, DEFENSE IN DEPTH: THE LINES OF TORRES

VEDRAS, COASTAL DEFENSES, FORTS & MARTELLOS)

THE ARMY’S CAMPAIGNS (THE LOW

COUNTRIES 1793-1795, INDIA, THE CAPE 1795, NORTH HOLLAND 1799, THE WEST INDIES,

EGYPT 1801, SOUTH AMERICA 1806-1807, VIMEIRO 1808, CORUNNA 1809, PORTUGAL &

TALAVERA 1809, BUSACO 1810, ALBUERA 1811, CIUDAD RODRIGO 1812, BADAJOZ 1812,

SALAMANCA 1812, VITTORIA 1813, PYRENEES AND SOUTHERN FRANCE, AMERICA AND CANADA

1812-1815, QUATRE BRAS 1815, WATERLOO 1815)

THE ROYAL NAVY AT WAR (HMS

VICTORY, LORD HORATIO NELSON, SHIPS CREW, ROYAL MARINES, SHIPS-OF-THE-LINE,

FRIGATES, SHIPYARDS AND EQUIPMENT)

NAVAL TACTICS (BREAKING THE LINE,

FRIGATE TACTICS)

THE NAVY’S CAMPAIGNS (TRAFALGAR

1805, THE GLORIOUS FIRST OF JUNE 1794, CAPE ST. VINCENT 1797, CAMPERDOWN 1797, THE

MEDITERRANEAN 1798, COPENHAGEN 1801, THE NAVAL CAMPAIGNS 1806-1815, AMPHIBIOUS

OPERATIONS)

SIR THOMAS LAWRENCE, THE DUKE OF

WELLINGTON

-------------------------------------

Additional Information from

Internet Encyclopedia

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley,

1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS (né Wesley; 1 May 1769 – 14

September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish statesman, soldier, and Tory politician who

was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain,

serving twice as prime minister of the United Kingdom. He is among the

commanders who won and ended the Napoleonic Wars when the Seventh Coalition

defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Wellesley was born into the

Protestant Ascendancy in County Meath or Dublin in Ireland (then known as the

Kingdom of Ireland). He was commissioned as an ensign in the British Army in

1787, serving in Ireland as aide-de-camp to two successive lords lieutenant of

Ireland. He was also elected as a member of Parliament in the Irish House of

Commons. He was a colonel by 1796 and saw action in the Netherlands and in

India, where he fought in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War at the Battle of

Seringapatam. He was appointed governor of Seringapatam and Mysore in 1799 and,

as a newly appointed major-general, won a decisive victory over the Maratha

Confederacy at the Battle of Assaye in 1803.

Wellesley rose to prominence as

a general during the Peninsular campaign of the Napoleonic Wars, and was

promoted to the rank of field marshal after leading the allied forces to

victory against the French Empire at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813. Following

Napoleon's exile in 1814, he served as the ambassador to France and was made

Duke of Wellington. During the Hundred Days in 1815, he commanded the allied

army which, together with a Prussian Army under Field Marshal Gebhard von

Blücher, defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. Wellington's battle record is

exemplary; he ultimately participated in some 60 battles during the course of

his military career.

Wellington is famous for his

adaptive defensive style of warfare, resulting in several victories against

numerically superior forces while minimising his own losses. He is regarded as

one of the greatest commanders in the modern era, and many of his tactics and

battle plans are still studied in military academies around the world. After

the end of his active military career, he returned to politics. He was twice

British prime minister as a member of the Tory party from 1828 to 1830 and for

a little less than a month in 1834. He oversaw the passage of the Roman

Catholic Relief Act 1829, while he opposed the Reform Act 1832. He continued as

one of the leading figures in the House of Lords until his retirement and

remained Commander-in-Chief of the British Army until his death.

Early life

Wellesley was born into an

aristocratic Anglo-Irish family, belonging to the Protestant Ascendancy,

beginning life as The Hon. Arthur Wesley.[3] Wellesley was born the son of

Anne, Countess of Mornington, and Garret Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington. His father

was himself the son of Richard Wesley, 1st Baron Mornington, and had a short

career in politics representing the constituency of Trim in the Irish House of

Commons before succeeding his father as Baron Mornington in 1758. Garret

Mornington was also an accomplished composer, and in recognition of his musical

and philanthropic achievements was elevated to the rank of Earl of Mornington

in 1760.[4] Wellesley's mother was the eldest daughter of Arthur Hill-Trevor,

1st Viscount Dungannon, after whom Wellesley was named. Through Elizabeth of

Rhuddlan, Wellesley was a descendant of Edward I.

Wellesley was the sixth of nine

children born to the Earl and Countess of Mornington. His siblings included

Richard, Viscount Wellesley, later 1st Marquess Wellesley, 2nd Earl of

Mornington, and Baron Maryborough.

Birth date and place

The exact date and location of

Wellesley's birth is not known; however, biographers mostly follow the same

contemporary newspaper evidence, which states that he was born on 1 May 1769,

the day before he was baptised in St. Peter's Church on Aungier Street in

Dublin. However, Ernest Lloyd states "registry of St. Peter's Church,

Dublin, shows that he was christened there on 30 April 1769". His

baptismal font was donated to St. Nahi's Church in Dundrum, Dublin, in 1914.

Wellesley may have been born at

his parents' townhouse, Mornington House at 6 Merrion Street (the address later

became known as 24 Upper Merrion Street), Dublin, which now forms part of the

Merrion Hotel.[12] His mother, Anne, Countess of Mornington, recalled in 1815

that he had been born at 6 Merrion Street.

His family's home at Dangan

Castle, Dangan near Summerhill, County Meath has also been purported to have

been his birth place. In his obituary, published in The Times in 1852, reported

that Dangan was unanimously believed to have been the place of his birth,

though suggested is was unlikely, but not impossible, that the family had

travelled to Dublin for his baptism.[15] A pillar was erected in his honour

near Dangan in 1817.

The place of his birth has been

much disputed following his death, with Sir. J.D. Burke writing the following

in 1873:

"Isn't it remarkable that

until recently all the old memoirs of the Duke of Wellington seemed to infer

that County Meath was the place of birth. Nowadays the theory that he was born

in Dublin is generally accepted but by no means proved".

Other places that have been put

forward as the location of his birth include a coach between Meath and Dublin,

the Dublin packet boat and the Wellesley townhouse in Trim, County Meath.

Childhood

Wellesley spent much of his

early childhood at his family's ancestral home, Dangan Castle in County Meath,

Ireland (engraving, 1842).

Wellesley spent most of his

childhood at his family's two homes, the first a large house in Dublin,

Mornington House, and the second Dangan Castle, 3 miles (5 km) north of

Summerhill in County Meath. In 1781, Arthur's father died and his eldest

brother Richard inherited his father's earldom.

He went to the diocesan school

in Trim when at Dangan, Mr Whyte's Academy when in Dublin, and Brown's School

in Chelsea when in London. He then enrolled at Eton College, where he studied

from 1781 to 1784. His loneliness there caused him to hate it, and makes it

highly unlikely that he actually said "The Battle of Waterloo was won on

the playing fields of Eton", a quotation which is often attributed to him.

Moreover, Eton had no playing fields at the time. In 1785, a lack of success at

Eton, combined with a shortage of family funds due to his father's death,

forced the young Wellesley and his mother to move to Brussels. Until his early

twenties, Arthur showed little sign of distinction and his mother grew

increasingly concerned at his idleness, stating, "I don't know what I

shall do with my awkward son Arthur."

In 1786, Arthur enrolled in the

French Royal Academy of Equitation in Angers, where he progressed

significantly, becoming a good horseman and learning French, which later proved

very useful. Upon returning to England later the same year, he astonished his

mother with his improvement.

Early military career

Despite his new promise,

Wellesley had yet to find a job and his family was still short of money, so

upon the advice of his mother, his brother Richard asked his friend the Duke of

Rutland (then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) to consider Arthur for a commission

in the Army. Soon afterward, on 7 March 1787, he was gazetted ensign in the

73rd Regiment of Foot. In October, with the assistance of his brother, he was

assigned as aide-de-camp, on ten shillings a day (twice his pay as an ensign),

to the new Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Buckingham. He was also transferred

to the new 76th Regiment forming in Ireland and on Christmas Day, 1787, was

promoted lieutenant. During his time in Dublin his duties were mainly social;

attending balls, entertaining guests and providing advice to Buckingham. While

in Ireland, he overextended himself in borrowing due to his occasional

gambling, but in his defence stated that "I have often known what it was

to be in want of money, but I have never got helplessly into debt".

On 23 January 1788, he

transferred into the 41st Regiment of Foot,[28] then again on 25 June 1789 he

transferred to the 12th (Prince of Wales's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons and,

according to military historian Richard Holmes, he also reluctantly entered

politics. Shortly before the general election of 1789, he went to the rotten

borough of Trim to speak against the granting of the title "Freeman"

of Dublin to the parliamentary leader of the Irish Patriot Party, Henry

Grattan. Succeeding, he was later nominated and duly elected as a Member of

Parliament (MP) for Trim in the Irish House of Commons. Because of the limited

suffrage at the time, he sat in a parliament where at least two-thirds of the

members owed their election to the landowners of fewer than a hundred boroughs.

Wellesley continued to serve at Dublin Castle, voting with the government in

the Irish parliament over the next two years. He became a captain on 30 January

1791, and was transferred to the 58th Regiment of Foot.

On 31 October, he transferred to

the 18th Light Dragoons and it was during this period that he grew increasingly

attracted to Kitty Pakenham, the daughter of Edward Pakenham, 2nd Baron

Longford. She was described as being full of 'gaiety and charm'. In 1793, he

proposed, but was turned down by her brother Thomas, 2nd Earl of Longford, who

considered Wellesley to be a young man, in debt, with very poor prospects.An

aspiring amateur musician, Wellesley, devastated by the rejection, burnt his

violins in anger, and resolved to pursue a military career in earnest.[38] He

became a major by purchase in the 33rd Regiment in 1793.A few months later, in

September, his brother lent him more money and with it he purchased a-colonelcy

in the 33rd.

Netherlands

In 1793, the Duke of York was

sent to Flanders in command of the British contingent of an allied force

destined for the invasion of France. In June 1794, Wellesley with the 33rd

regiment set sail from Cork bound for Ostend as part of an expedition bringing

reinforcements for the army in Flanders. They arrived too late to participate,

and joined the Duke of York as he was pulling back towards the Netherlands. On

15 September 1794, at the Battle of Boxtel,[42] east of Breda, Wellington, in

temporary command of his brigade, had his first experience of battle. During

General Abercromby's withdrawal in the face of superior French forces, the 33rd

held off enemy cavalry, allowing neighbouring units to retreat safely. During

the extremely harsh winter that followed, Wellesley and his regiment formed

part of an allied force holding the defence line along the Waal River. The

33rd, along with the rest of the army, suffered heavy losses from attrition and

illness. Wellesley's health was also affected by the damp environment.

Though the campaign was to end

disastrously, with the British army driven out of the United Provinces into the

German states, Wellesley became more aware of battle tactics, including the use

of lines of infantry against advancing columns, and the merits of supporting

sea-power. He understood that the failure of the campaign was due in part to

the faults of the leaders and the poor organisation at headquarters.[44] He

remarked later of his time in the Netherlands that "At least I learned

what not to do, and that is always a valuable lesson".

Returning to England in March

1795, he was reinstated as a member of parliament for Trim.[45] He hoped to be

given the position of secretary of war in the new Irish government but the new

lord-lieutenant, Lord Camden, was only able to offer him the post of

Surveyor-General of the Ordnance. Declining the post, he returned to his

regiment, now at Southampton preparing to set sail for the West Indies. After

seven weeks at sea, a storm forced the fleet back to Poole. The 33rd was given

time to recuperate and a few months later, Whitehall decided to send the

regiment to India. Wellesley was promoted full colonel by seniority on 3 May

1796[46] and a few weeks later set sail for Calcutta with his regiment.

India

Arriving in Calcutta in February

1797 he spent 5 months there, before being sent in August to a brief expedition

to the Philippines, where he established a list of new hygiene precautions for

his men to deal with the unfamiliar climate.[48] Returning in November to

India, he learnt that his elder brother Richard, now known as Lord Mornington,

had been appointed as the new Governor-General of India.

In 1798, he changed the spelling

of his surname to "Wellesley"; up to this time he was still known as

Wesley, which his eldest brother considered the ancient and proper

spelling.[49][50]

Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

As part of the campaign to

extend the rule of the British East India Company, the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

broke out in 1798 against the Sultan of Mysore, Tipu Sultan.[51] Arthur's

brother Richard ordered that an armed force be sent to capture Seringapatam and

defeat Tipu. During the war, rockets were used on several occasions. Wellesley

was almost defeated by Tipu's Diwan, Purnaiah, at the Battle of Sultanpet Tope.

Quoting Forrest,

At this point (near the village

of Sultanpet, Figure 5) there was a large tope, or grove, which gave shelter to

Tipu's rocketmen and had obviously to be cleaned out before the siege could be

pressed closer to Srirangapattana island. The commander chosen for this

operation was Col. Wellesley, but advancing towards the tope after dark on the

5th April 1799, he was set upon with rockets and musket-fires, lost his way

and, as Beatson politely puts it, had to "postpone the attack" until

a more favourable opportunity should offer.

The following day, Wellesley

launched a fresh attack with a larger force, and took the whole position

without any killed in action. On 22 April 1799, twelve days before the main

battle, rocketeers maneuvered to the rear of the British encampment, then

'threw a great number of rockets at the same instant' to signal the beginning

of an assault by 6,000 Indian infantry and a corps of Frenchmen, all ordered by

Mir Golam Hussain and Mohomed Hulleen Mir Miran. The rockets had a range of

about 1,000 yards. Some burst in the air like shells. Others, called ground

rockets, would rise again on striking the ground and bound along in a serpentine

motion until their force was spent. According to one British observer, a young

English officer named Bayly: "So pestered were we with the rocket boys

that there was no moving without danger from the destructive missiles

...". He continued:

The rockets and musketry from

20,000 of the enemy were incessant. No hail could be thicker. Every

illumination of blue lights was accompanied by a shower of rockets, some of

which entered the head of the column, passing through to the rear, causing

death, wounds, and dreadful lacerations from the long bamboos of twenty or

thirty feet, which are invariably attached to them.

Under the command of General

Harris, some 24,000 troops were dispatched to Madras (to join an equal force

being sent from Bombay in the west). Arthur and the 33rd sailed to join them in

August.

After extensive and careful

logistic preparation (which would become one of Wellesley's main

attributes)[56] the 33rd left with the main force in December and travelled

across 250 miles (402 km) of jungle from Madras to Mysore. On account of his

brother, during the journey, Wellesley was given an additional command, that of

chief advisor to the Nizam of Hyderabad's army (sent to accompany the British

force). This position was to cause friction among many of the senior officers

(some of whom were senior to Wellesley).[57] Much of this friction was put to

rest after the Battle of Mallavelly, some 20 miles (32 km) from Seringapatam,

in which Harris' army attacked a large part of the sultan's army. During the

battle, Wellesley led his men, in a line of battle of two ranks, against the

enemy to a gentle ridge and gave the order to fire. After an extensive

repetition of volleys, followed by a bayonet charge, the 33rd, in conjunction

with the rest of Harris's force, forced Tipu's infantry to retreat.

Seringapatam

Immediately after their arrival

at Seringapatam on 5 April 1799, the Battle of Seringapatam began and Wellesley

was ordered to lead a night attack on the village of Sultanpettah, adjacent to

the fortress to clear the way for the artillery.[60] Because of a variety of

factors including the Mysorean army's strong defensive preparations and the

darkness the attack failed with 25 casualties due to confusion among the

British. Wellesley suffered a minor injury to his knee from a spent

musket-ball.[61][62] Although they would re-attack successfully the next day,

after time to scout ahead the enemy's positions, the affair affected Wellesley.

He resolved "never to attack an enemy who is preparing and strongly

posted, and whose posts have not been reconnoitred by daylight".[53] Lewin

Bentham Bowring gives this alternative account:

One of these groves, called the

Sultanpet Tope, was intersected by deep ditches, watered from a channel running

in an easterly direction about a mile from the fort. General Baird was directed

to scour this grove and dislodge the enemy, but on his advancing with this

object on the night of the 5th, he found the tope unoccupied. The next day,

however, the Mysore troops again took possession of the ground, and as it was

absolutely necessary to expel them, two columns were detached at sunset for the

purpose. The first of these, under Colonel Shawe, got possession of a ruined

village, which it successfully held. The second column, under Colonel

Wellesley, on advancing into the tope, was at once attacked in the darkness of

night by a tremendous fire of musketry and rockets. The men, floundering about

amidst the trees and the water-courses, at last broke, and fell back in

disorder, some being killed and a few taken prisoners. In the confusion Colonel

Wellesley was himself struck on the knee by a spent ball, and narrowly escaped

falling into the hands of the enemy.

A few weeks later, after

extensive artillery bombardment, a breach was opened in the main walls of the

fortress of Seringapatam.[53] An attack led by Major-General Baird secured the

fortress. Wellesley secured the rear of the advance, posting guards at the

breach and then stationed his regiment at the main palace.[64] After hearing

news of the death of the Tipu Sultan, Wellesley was the first at the scene to

confirm his death, checking his pulse.[65] Over the coming day, Wellesley grew

increasingly concerned over the lack of discipline among his men, who drank and

pillaged the fortress and city. To restore order, several soldiers were flogged

and four hanged.

After battle and the resulting

end of the war, the main force under General Harris left Seringapatam and

Wellesley, aged 30, stayed behind to command the area as the new Governor of

Seringapatam and Mysore. While in India, Wellesley was ill for a considerable

time, first with severe diarrhoea from the water and then with fever, followed

by a serious skin infection caused by trichophyton.

Wellesley was in charge of

raising an Anglo-Indian expeditionary force in Trincomali in early 1801 for the

capture of Batavia and Mauritius from the French. However, on the eve of its

departure, orders arrived from England that it was to be sent to Egypt to

co-operate with Sir Ralph Abercromby in the expulsion of the French from Egypt.

Wellesley had been appointed second in command to Baird, but owing to ill

health did not accompany the expedition on 9 April 1801. This was fortunate for

Wellesley, since the vessel on which he was to have sailed sank in the Red Sea.

He was promoted to

brigadier-general on 17 July 1801. He took residence within the Sultan's summer

palace and reformed the tax and justice systems in his province to maintain

order and prevent bribery.

Dhoondiah Waugh insurgency

In 1800, whilst serving as

Governor of Mysore, Wellesley was tasked with putting down an insurgency led by

Dhoondiah Waugh, formerly a Patan trooper for Tipu Sultan.[70] Having escaped

after the fall of Seringapatam he became a powerful brigand, raiding villages

along the Maratha–Mysore border region.

Despite initial setbacks, the

East India Company having pursued and destroyed his forces once already,

forcing him into retreat in August 1799, he raised a sizeable force composed of

disbanded Mysore soldiers, captured small outposts and forts in Mysore, and was

receiving the support of several Maratha killedars opposed to British

occupation.[72] This drew the attention of the British administration, who were

beginning to recognise him as more than just a bandit, as his raids, expansion

and threats to destabilise British authority suddenly increased in 1800.[73]

The death of Tipu Sultan had created a power vacuum and Waugh was seeking to

fill it.

Given independent command of a

combined East India Company and British Army force,[74] Wellesley ventured

north to confront Waugh in June 1800, with an army of 8,000 infantry and

cavalry, having learnt that Waugh's forces numbered over 50,000, although the

majority (around 30,000) were irregular light cavalry and unlikely to pose a

serious threat to British infantry and artillery.

Throughout June–August 1800,

Wellesley advanced through Waugh's territory, his troops escalading forts in

turn and capturing each one with "trifling loss".[76] The forts

generally offered little resistance due to their poor construction and design.[74]

Wellesley did not have sufficient troops to garrison each fort and had to clear

the surrounding area of insurgents before advancing to the next fort.[77] On 31

July, he had "taken and destroyed Dhoondiah's baggage and six guns, and

driven into the Malpoorba (where they were drowned) about five thousand

people".[78] Dhoondiah continued to retreat, but his forces were rapidly

deserting, he had no infantry and due to the monsoon weather flooding river

crossings he could no longer outpace the British advance.[79] On 10 September,

at the Battle of Conaghul, Wellesley personally led a charge of 1,400 British

dragoons and Indian cavalry, in single line with no reserve, against Dhoondiah

and his remaining 5,000 cavalry.[79] Dhoondiah was killed during the clash, his

body was discovered and taken to the British camp tied to a cannon. With this

victory, Wellesley's campaign was concluded, and British authority had been

restored.[80] Wellesley then paid for the future upkeep of Dhoondiah's orphaned

son.

Second Anglo-Maratha War

In September 1802, Wellesley

learnt that he had been promoted to the rank of major-general. He had been

gazetted on 29 April 1802, but the news took several months to reach him by

sea. He remained at Mysore until November when he was sent to command an army

in the Second Anglo-Maratha War.

When he determined that a long

defensive war would ruin his army, Wellesley decided to act boldly to defeat

the numerically larger force of the Maratha Empire.[83] With the logistic

assembly of his army complete (24,000 men in total) he gave the order to break

camp and attack the nearest Maratha fort on 8 August 1803.[84] The fort

surrendered on 12 August after an infantry attack had exploited an

artillery-made breach in the wall. With the fort now in British control

Wellesley was able to extend control southwards to the river Godavari.

Assaye, Argaum and Gawilghur

Splitting his army into two

forces to pursue and locate the main Marathas army (the second force, commanded

by Colonel Stevenson was far smaller), Wellesley was preparing to rejoin his

forces on 24 September. His intelligence, however, reported the location of the

Marathas' main army, between two rivers near Assaye.[87] If he waited for the

arrival of his second force, the Marathas would be able to mount a retreat, so

Wellesley decided to launch an attack immediately.

On 23 September, Wellesley led

his forces over a ford in the river Kaitna and the Battle of Assaye

commenced.[88] After crossing the ford the infantry was reorganised into

several lines and advanced against the Maratha infantry. Wellesley ordered his

cavalry to exploit the flank of the Maratha army just near the village.[88]

During the battle Wellesley himself came under fire; two of his horses were

shot from under him and he had to mount a third.[89] At a crucial moment,

Wellesley regrouped his forces and ordered Colonel Maxwell (later killed in the

attack) to attack the eastern end of the Maratha position while Wellesley

himself directed a renewed infantry attack against the centre.

An officer in the attack wrote

of the importance of Wellesley's personal leadership: "The General was in

the thick of the action the whole time ... I never saw a man so cool and

collected as he was ... though I can assure you, till our troops got the order

to advance the fate of the day seemed doubtful ..."[90] With some 6,000

Marathas killed or wounded, the enemy was routed, though Wellesley's force was

in no condition to pursue. British casualties were heavy: the British losses

amounted to 428 killed, 1,138 wounded and 18 missing (the British casualty

figures were taken from Wellesley's own despatch).[91] Wellesley was troubled

by the loss of men and remarked that he hoped "I should not like to see

again such loss as I sustained on 23 September, even if attended by such

gain".[86] Years later, however, he remarked that Assaye and not Waterloo

was the best battle he ever fought.

Despite the damage done to the

Maratha army, the battle did not end the war.[92] A few months later in

November, Wellesley attacked a larger force near Argaum, leading his army to

victory again, with an astonishing 5,000 enemy dead at the cost of only 361

British casualties.[92] A further successful attack at the fortress at

Gawilghur, combined with the victory of General Lake at Delhi, forced the

Maratha to sign a peace settlement at Anjangaon (not concluded until a year

later) called the Treaty of Surji-Anjangaon.

Military historian Richard

Holmes remarked that Wellesley's experiences in India had an important

influence on his personality and military tactics, teaching him much about

military matters that would prove vital to his success in the Peninsular

War.[94] These included a strong sense of discipline through drill and

order,[95] the use of diplomacy to gain allies, and the vital necessity of a

secure supply line. He also established high regard for the acquisition of

intelligence through scouts and spies.[95] His personal tastes also developed,

including dressing himself in white trousers, a dark tunic, with Hessian boots

and black cocked hat (that later became synonymous as his style).

Leaving India

Wellesley had grown tired of his

time in India, remarking "I have served as long in India as any man ought

who can serve anywhere else". In June 1804 he applied for permission to

return home and as a reward for his service in India he was made a Knight of

the Bath in September. While in India, Wellesley had amassed a fortune of

£42,000 (considerable at the time, equivalent to £3.3 million in 2019),

consisting mainly of prize money from his campaign. When his brother's term as

Governor-General of India ended in March 1805, the brothers returned together

to England on HMS Howe. Wellesley, coincidentally, stopped on his voyage at the

island of Saint Helena and stayed in the same building in which Napoleon I

would live during his later exile.

Return to Britain

In September 1805, Major-General

Wellesley was newly returned from his campaigns in India and was not yet

particularly well known to the public. He reported to the office of the

Secretary of State for War and the Colonies to request a new assignment. In the

waiting room, he met Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, already a known figure after

his victories at the Nile and Copenhagen, who was briefly in England after

months pursuing the French Toulon fleet to the West Indies and back. Some 30

years later, Wellington recalled a conversation that Nelson began with him

which Wellesley found "almost all on his side in a style so vain and silly

as to surprise and almost disgust me".[99] Nelson left the room to inquire

who the young general was and, on his return, switched to a very different

tone, discussing the war, the state of the colonies, and the geopolitical

situation as between equals.[100] On this second discussion, Wellington

recalled, "I don't know that I ever had a conversation that interested me

more".[101] This was the only time that the two men met; Nelson was killed

at his victory at Trafalgar seven weeks later.

Wellesley then served in the

abortive Anglo-Russian expedition to north Germany in 1805, taking a brigade to

Elbe.

He then took a period of

extended leave from the army and was elected as a Tory member of the British

parliament for Rye in January 1806.[103][104] A year later, he was elected MP

for Newport on the Isle of Wight, and was then appointed to serve as Chief

Secretary for Ireland under the Duke of Richmond. At the same time, he was made

a privy counsellor.[103] While in Ireland, he gave a verbal promise that the

remaining Penal Laws would be enforced with great moderation, perhaps an

indication of his later willingness to support Catholic emancipation.[105]

Wellesley was described as having been "handsome, very brown, quite bald

and a hooked nose".

War against Denmark-Norway

Wellesley was in Ireland in May

1807 when he heard of the British expedition to Denmark-Norway. He decided to

go, while maintaining his political appointments, and was appointed to command

an infantry brigade in the Second Battle of Copenhagen, which took place in

August. He fought at Køge, during which the men under his command took 1,500

prisoners, with Wellesley later present during the surrender.

By 30 September, he had returned

to England and was raised to the rank of lieutenant general on 25 April

1808.[103] In June 1808 he accepted the command of an expedition of 9,000 men.

Preparing to sail for an attack on the Spanish colonies in South America (to

assist the Latin American patriot Francisco de Miranda) his force was instead

ordered to sail for Portugal, to take part in the Peninsular Campaign and

rendezvous with 5,000 troops from Gibraltar.

Peninsular War

1808–1809

Ready for battle, Wellesley left

Cork on 12 July 1808 to participate in the war against French forces in the

Iberian Peninsula, with his skills as a commander tested and

developed.[107]According to the historian Robin Neillands:

Wellesley had by now acquired

the experience on which his later successes were founded. He knew about command

from the ground up, about the importance of logistics, about campaigning in a

hostile environment. He enjoyed political influence and realised the need to

maintain support at home. Above all, he had gained a clear idea of how, by

setting attainable objectives and relying on his own force and abilities, a

campaign could be fought and won.

Wellesley defeated the French at

the Battle of Roliça and the Battle of Vimeiro in 1808[109] but was superseded

in command immediately after the latter battle. General Dalrymple then signed

the controversial Convention of Sintra, which stipulated that the Royal Navy

transport the French army out of Lisbon with all their loot, and insisted on

the association of the only available government minister, Wellesley.[109]

Dalrymple and Wellesley were recalled to Britain to face a Court of Enquiry.

Wellesley had agreed to sign the preliminary armistice, but had not signed the

convention, and was cleared.

Simultaneously, Napoleon entered

Spain with his veteran troops to put down the revolt; the new commander of the

British forces in the Peninsula, Sir John Moore, died during the Battle of

Corunna in January 1809.

Although overall the land war

with France was not going well from a British perspective, the Peninsula was

the one theatre where they, with the Portuguese, had provided strong resistance

against France and her allies. This contrasted with the disastrous Walcheren

expedition, which was typical of the mismanaged British operations of the time.

Wellesley submitted a memorandum to Lord Castlereagh on the defence of

Portugal. He stressed its mountainous frontiers and advocated Lisbon as the

main base because the Royal Navy could help to defend it. Castlereagh and the

cabinet approved the memo and appointed him head of all British forces in

Portugal.

Wellesley arrived in Lisbon on

22 April 1809 on board HMS Surveillante,[113] after narrowly escaping

shipwreck.[114] Reinforced, he took to the offensive. In the Second Battle of

Porto he crossed the Douro river in a daylight coup de main, and routed Marshal

Soult's French troops in Porto.

With Portugal secured, Wellesley

advanced into Spain to unite with General Cuesta's forces. The combined allied

force prepared for an assault on Marshal Victor's I Corps at Talavera, 23 July.

Cuesta, however, was reluctant to agree, and was only persuaded to advance on

the following day.[116] The delay allowed the French to withdraw, but Cuesta

sent his army headlong after Victor, and found himself faced by almost the

entire French army in New Castile—Victor had been reinforced by the Toledo and

Madrid garrisons. The Spanish retreated precipitously, necessitating the

advance of two British divisions to cover their retreat.

The next day, 27 July, at the

Battle of Talavera the French advanced in three columns and were repulsed

several times throughout the day by Wellesley, but at a heavy cost to the

British force. In the aftermath Marshal Soult's army was discovered to be advancing

south, threatening to cut Wellesley off from Portugal. Wellesley moved east on

3 August to block it, leaving 1,500 wounded in the care of the Spanish,[118]

intending to confront Soult before finding out that the French were in fact

30,000 strong. The British commander sent the Light Brigade on a dash to hold

the bridge over the Tagus at Almaraz. With communications and supply from

Lisbon secured for now, Wellesley considered joining with Cuesta again but

found out that his Spanish ally had abandoned the British wounded to the French

and was thoroughly uncooperative, promising and then refusing to supply the

British forces, aggravating Wellesley and causing considerable friction between

the British and their Spanish allies. The lack of supplies, coupled with the

threat of French reinforcement (including the possible inclusion of Napoleon

himself) in the spring, led to the British deciding to retreat into Portugal.

Following his victory at

Talavera, Wellesley was elevated to the Peerage of the United Kingdom on 26

August 1809 as Viscount Wellington of Talavera and of Wellington, in the County

of Somerset, with the subsidiary title of Baron Douro of Wellesley.

1810–1812

In 1810, a newly enlarged French

army under Marshal André Masséna invaded Portugal. British opinion was negative

and there were suggestions to evacuate Portugal. Instead, Lord Wellington first

slowed the French at Buçaco;[122] he then prevented them from taking the Lisbon

Peninsula by the construction of massive earthworks, known as the Lines of

Torres Vedras, which had been assembled in complete secrecy with their flanks

guarded by the Royal Navy.[123] The baffled and starving French invasion forces

retreated after six months. Wellington's pursuit was hindered by a series of

reverses inflicted by Marshal Ney in a much-lauded rear guard campaign.

In 1811, Masséna returned toward

Portugal to relieve Almeida; Wellington narrowly checked the French at the

Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro.[125] Simultaneously, his subordinate, Viscount

Beresford, fought Soult's 'Army of the South' to a bloody stalemate at the

Battle of Albuera in May.[126] Wellington was promoted to full general on 31

July for his services. The French abandoned Almeida, avoiding British

pursuit,[127] but retained the twin Spanish fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and

Badajoz, the 'Keys' guarding the roads through the mountain passes into

Portugal.

After taking the small

fortresses of Pamplona, Wellington invested San Sebastián but was frustrated by

the obstinate French garrison, losing 693 dead and 316 captured in a failed

assault and suspending the siege at the end of July. Soult's relief attempt was

blocked by the Spanish Army of Galicia at San Marcial, allowing the Allies to

consolidate their position and tighten the ring around the city, which fell in

September after a second spirited defence.[138] Wellington then forced Soult's

demoralised and battered army into a fighting retreat into France, punctuated

by battles at the Pyrenees,[139] Bidassoa and Nivelle.[140][141] Wellington

invaded southern France, winning at the Nive and Orthez.[142] Wellington's

final battle against his rival Soult occurred at Toulouse, where the Allied

divisions were badly mauled storming the French redoubts, losing some 4,600

men. Despite this momentary victory, news arrived of Napoleon's defeat and

abdication[143] and Soult, seeing no reason to continue the fighting, agreed on

a ceasefire with Wellington, allowing Soult to evacuate the city.

Hailed as the conquering hero by

the British, on 3 May 1814 Wellington was made Duke of Wellington, in the

county of Somerset, together with the subsidiary title of Marquess Douro, in

said County.

He received some recognition

during his lifetime (the title of "Duque de Ciudad Rodrigo" and

"Grandee of Spain") and the Spanish King Ferdinand VII allowed him to

keep part of the works of art from the Royal Collection which he had recovered

from the French. His equestrian portrait features prominently in the Monument

to the Battle of Vitoria, in present-day Vitoria-Gasteiz.

Wellington (far left) alongside

Metternich, Talleyrand and other European diplomats at the Congress of Vienna,

1815 (engraving after Jean-Baptiste Isabey)

His popularity in Britain was

due to his image and his appearance as well as to his military triumphs. His

victory fitted well with the passion and intensity of the Romantic movement,

with its emphasis on individuality. His personal style influenced the fashions

in Britain at the time: his tall, lean figure and his plumed black hat and

grand yet classic uniform and white trousers became very popular.

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was

fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United

Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). It commenced with a diversionary

attack on Hougoumont by a division of French soldiers. After a barrage of 80

cannons, the first French infantry attack was launched by Comte D'Erlon's I

Corps. D'Erlon's troops advanced through the Allied centre, resulting in Allied

troops in front of the ridge retreating in disorder through the main position.

D'Erlon's corps stormed the most fortified Allied position, La Haye Sainte, but

failed to take it. An Allied division under Thomas Picton met the remainder of

D'Erlon's corps head to head, engaging them in an infantry duel in which Picton

was killed. During this struggle Lord Uxbridge launched two of his cavalry

brigades at the enemy, catching the French infantry off guard, driving them to

the bottom of the slope, and capturing two French Imperial Eagles. The charge,

however, over-reached itself, and the British cavalry, crushed by fresh French

horsemen sent at them by Napoleon, were driven back, suffering tremendous

losses.

Shortly before 16:00, Marshal

Ney noted an apparent withdrawal from Wellington's centre. He mistook the

movement of casualties to the rear for the beginnings of a retreat, and sought

to exploit it. Ney at this time had few infantry reserves left, as most of the

infantry had been committed either to the futile Hougoumont attack or to the

defence of the French right. Ney, therefore, tried to break Wellington's centre

with a cavalry charge alone.

The Grenadiers à Cheval.

Napoleon can be seen in the background on a grey horse. A number of different

mounts could have been ridden by Napoleon at Waterloo: Ali, Crebère, Désirée,

Jaffa, Marie, and Tauris.[161]

At about 16:30, the first

Prussian corps arrived. Commanded by Freiherr von Bülow, IV Corps arrived as

the French cavalry attack was in full spate. Bülow sent the 15th Brigade to

link up with Wellington's left flank in the Frichermont–La Haie area while the

brigade's horse artillery battery and additional brigade artillery deployed to

its left in support.[162] Napoleon sent Lobau's corps to intercept the rest of

Bülow's IV Corps proceeding to Plancenoit. The 15th Brigade sent Lobau's corps

into retreat to the Plancenoit area. Von Hiller's 16th Brigade also pushed

forward with six battalions against Plancenoit. Napoleon had dispatched all

eight battalions of the Young Guard to reinforce Lobau, who was now seriously

pressed by the enemy. Napoleon's Young Guard counter-attacked and, after very

hard fighting, secured Plancenoit, but were themselves counter-attacked and

driven out.[163] Napoleon then resorted to sending two battalions of the Middle

and Old Guard into Plancenoit and after ferocious fighting they recaptured the

village.[163] The French cavalry attacked the British infantry squares many

times, each at a heavy cost to the French but with few British casualties. Ney

himself was displaced from his horse four times.[164] Eventually, it became

obvious, even to Ney, that cavalry alone were achieving little. Belatedly, he

organised a combined-arms attack, using Bachelu's division and Tissot's

regiment of Foy's division from Reille's II Corps plus those French cavalry

that remained in a fit state to fight. This assault was directed along much the

same route as the previous heavy cavalry attacks.

Wellington at the battle of

Waterloo

The French army now fiercely

attacked the Coalition all along the line with the culminating point being

reached when Napoleon sent forward the Imperial Guard at 19:30. The attack of

the Imperial Guards was mounted by five battalions of the Middle Guard, and not

by the Grenadiers or Chasseurs of the Old Guard. Marching through a hail of

canister and skirmisher fire and severely outnumbered, the 3,000 or so Middle

Guardsmen advanced to the west of La Haye Sainte and proceeded to separate into

three distinct attack forces. One, consisting of two battalions of Grenadiers,

defeated the Coalition's first line and marched on. Chassé's relatively fresh

Dutch division was sent against them, and Allied artillery fired into the

victorious Grenadiers' flank. This still could not stop the Guard's advance, so

Chassé ordered his first brigade to charge the outnumbered French, who faltered

and broke.

British 10th Hussars of Vivian's

Brigade (red shakos – blue uniforms) attacking mixed French troops, including a

square of Guard grenadiers (left, middle distance) in the final stages of the

battle

Further to the west, 1,500

British Foot Guards under Maitland were lying down to protect themselves from

the French artillery. As two battalions of Chasseurs approached, the second

prong of the Imperial Guard's attack, Maitland's guardsmen rose and devastated

them with point-blank volleys. The Chasseurs deployed to counter-attack but

began to waver. A bayonet charge by the Foot Guards then broke them. The third

prong, a fresh Chasseur battalion, now came up in support. The British

guardsmen retreated with these Chasseurs in pursuit, but the latter were halted

as the 52nd Light Infantry wheeled in line onto their flank and poured a

devastating fire into them and then charged.[167][168] Under this onslaught,

they too broke.

The last of the Guard retreated

headlong. Mass panic ensued through the French lines as the news spread:

"La Garde recule. Sauve qui peut!" ("The Guard is retreating.

Every man for himself!"). Wellington then stood up in Copenhagen's stirrups,

and waved his hat in the air to signal an advance of the Allied line just as

the Prussians were overrunning the French positions to the east. What remained

of the French army then abandoned the field in disorder. Wellington and Blücher

met at the inn of La Belle Alliance, on the north–south road which bisected the

battlefield, and it was agreed that the Prussians should pursue the retreating

French army back to France.[167] The Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November

1815.

After the victory, the Duke

supported proposals that a medal be awarded to all British soldiers who

participated in the Waterloo campaign, and on 28