RMS

QUEEN MARY BLUE RIBAND TRANS ATLANTIC BRITISH OCEAN LINER WW2 TROOPSHIP

IMAGES OF AMERICA SOFTBOUND BOOK

in ENGLISH by SUZANNE TARBELL COOPER, FRANK COOPER, ATHENE MIHALAKIS KOVACIC,

DON LYNCH, JOHN THOMAS and THE QUEEN MARY ARCHIVES

---------------------------

Additional Information from Internet

Encyclopedia

RMS Queen Mary is a retired

British ocean liner that sailed primarily on the North Atlantic Ocean from 1936

to 1967 for the Cunard Line and was built by John Brown & Company in

Clydebank, Scotland. Queen Mary, along with RMS Queen Elizabeth,[4] was built

as part of Cunard's planned two-ship weekly express service between

Southampton, Cherbourg and New York. The two ships were a British response to

the express superliners built by German, Italian and French companies in the

late 1920s and early 1930s.

Queen Mary sailed on her maiden

voyage on 27 May 1936 and won the Blue Riband that August; she lost the title

to SS Normandie in 1937 and recaptured it in 1938, holding it until 1952, when

it was taken by the new SS United States. With the outbreak of World War II,

she was converted into a troopship and ferried Allied soldiers during the conflict.

On one voyage in 1943, she carried over 16,600 people, the still-standing

record for the most people on a vessel.

Following the war, Queen Mary

was refitted for passenger service and along with Queen Elizabeth commenced the

two-ship transatlantic passenger service for which the two ships were initially

built. The two ships dominated the transatlantic passenger transportation

market until the dawn of the jet age in the late 1950s. By the mid-1960s, Queen

Mary was ageing and was operating at a loss.

After several years of decreased

profits for Cunard Line, Queen Mary was officially retired from service in

1967. She left Southampton for the last time on 31 October 1967 and sailed to

the port of Long Beach, California, United States, where she was permanently

moored. The City of Long Beach bought the ship to serve as a tourist attraction

featuring restaurants, a museum and a hotel. The city contracted out management

of the ship to various third-party firms over the years. It took back

operational control in 2021.

With Weimar Germany launching

Bremen and Europa into service, Britain did not want to be left behind in the

shipbuilding race. White Star Line began construction on their 80,000-ton

Oceanic in 1928, while Cunard planned a 75,000-ton unnamed ship of their own.

Construction on the ship, then

known only as "Hull Number 534", began in December 1930 on the River

Clyde by the John Brown & Company shipyard at Clydebank in Scotland. Work

was halted in December 1931 due to the Great Depression and Cunard applied to

the British Government for a loan to complete 534. The loan was granted, with

enough money to complete the unfinished ship, and also to build a running mate,

with the intention to provide a two ship weekly service to New York.

One condition of the loan was

that Cunard merge with the White Star Line,[8] another struggling British

shipping company, which was Cunard's chief British rival at the time and which

had already been forced by the depression to cancel construction of its

Oceanic. Both lines agreed and the merger was completed on 10 May 1934. Work on

Queen Mary resumed immediately and she was launched on 26 September 1934.

Completion ultimately took 3+1⁄2 years and cost 3.5 million pounds sterling,[7]

then equal to $17.5 million (equivalent to $310 million in 2023). Much of the

ship's interior was designed and constructed by the Bromsgrove Guild.[9] Prior

to the ship's launch, the River Clyde had to be specifically deepened to cope

with her size, this being undertaken by the engineer D. Alan Stevenson.

The ship was named after Mary of

Teck, consort of King George V. Until her launch, the name was kept a closely

guarded secret. Legend has it that Cunard intended to name the ship Victoria,

in keeping with company tradition of giving its ships names ending in

"ia", but when company representatives asked the King's permission to

name the ocean liner after Britain's "greatest Queen", he said his

wife, Mary of Teck, would be delighted.[11] And so, the legend goes, the

delegation had, of course, no other choice but to report that No. 534 would be

called Queen Mary.

This story has always been

denied by company officials, and traditionally the names of royal family

members have only been used for capital ships of the Royal Navy. This anecdote

has been widely contested ever since Frank Braynard published it in his 1947

book, Lives of the Liners. Some support for the story was provided by

Washington Post editor Felix Morley, who sailed as a guest of the Cunard Line

on Queen Mary's 1936 maiden voyage. In his 1979 autobiography, For the Record,

Morley wrote that he was placed at a table with Sir Percy Bates, chairman of

the Cunard Line. Bates told him the story of the naming of the ship "on

condition you won't print it during my lifetime." The story was finally

proven in 1988 when Braynard attended the same dinner party as Eleanor Sparkes,

daughter of Sir Ashley Sparkes, who'd been with Bates during the conversation

with George V. She confirmed the "favourite ship story" to him,

telling the exact anecdote that Braynard had published in his book.

Despite this, Cunard still

denies the name change. It is also possible the name Queen Mary was decided

upon as a compromise between Cunard and the White Star Line, as both lines had

naming traditions. White Star used names ending in "ic", while Cunard

used names ending in "ia".

The name had already been given

to the Clyde turbine steamer TS Queen Mary, so Cunard made an arrangement with

its owners and this older ship was renamed Queen Mary II.

Queen Mary was fitted with 24

Yarrow boilers in four boiler rooms and four Parsons turbines in two engine

rooms. The boilers delivered 400 pounds per square inch (28 bar) steam at 700

°F (371 °C) which provided a maximum of 212,000 shp (158,000 kW) to four

propellers, each turning at 200 RPM.

Pre-Second World War

In 1934 the new liner was

launched by Her Majesty Queen Mary as RMS Queen Mary. On her way down the

slipway, Queen Mary was slowed by eighteen drag chains, which checked the

liner's progress into the River Clyde, a portion of which had been widened to

accommodate the launch.

When she sailed on her maiden

voyage from Southampton on 27 May 1936, she was commanded by Sir Edgar Britten,

who had been the master designate for Cunard White Star whilst the ship was

under construction at the John Brown shipyard. Queen Mary measured 80,774 gross

register tons (GRT), making her the world's largest passenger ship.[18] Her

rival Normandie, only measured 79,280 GRT. Queen Mary sailed at high speed for

most of her maiden voyage to New York, until heavy fog forced a reduction of

speed on the final day of the crossing, arriving in New York Harbor on 1 June

1936.

Queen Mary's design was

criticised for being too traditional, especially when Normandie's hull was

revolutionary with a clipper-shaped, streamlined bow. Except for her cruiser

stern, she seemed to be an enlarged version of her Cunard predecessors from the

pre-First World War era. Her interior design, while mostly Art Deco, seemed

restrained and conservative when compared to the ultramodern French liner.

Nonetheless Queen Mary proved to be the more popular vessel than her rival, in

terms of passengers carried.

In August 1936, Queen Mary

captured the Blue Riband from Normandie, with average speeds of 30.14 knots

(55.82 km/h; 34.68 mph) westbound and 30.63 knots (56.73 km/h; 35.25 mph)

eastbound. That same month, Normandie returned to service after a refit that increased

her size to 83,243 GRT, reclaiming the title of world's largest passenger

ship.[20] In 1937, Normandie received a new set of propellers and reclaimed the

Blue Riband. However, in 1938, under the command of Robert B. Irving, Queen

Mary took back the Blue Riband in both directions,[21] with average speeds of

30.99 knots (57.39 km/h; 35.66 mph) westbound and 31.69 knots (58.69 km/h;

36.47 mph) eastbound, records which stood until lost to United States in 1952.

Interior

Among facilities available on

board Queen Mary, the liner featured two indoor swimming pools, beauty salons,

libraries and children's nurseries for all three classes, a music studio and

lecture hall, telephone connectivity to anywhere in the world, outdoor paddle

tennis courts and dog kennels. The largest room on board was the cabin class

(first class) main dining room (grand salon), spanning three stories in height

and anchored by wide columns. The ship had many air-conditioned public rooms on

board. The cabin-class swimming pool facility spanned over two decks in height.

This was the first ocean liner to be equipped with her own Jewish prayer room –

part of a policy to show that British shipping lines avoided the antisemitism

evident in Nazi Germany.

The cabin-class main dining room

featured a large map of the transatlantic crossing, with twin tracks

symbolising the winter/spring route (further south to avoid icebergs) and the

summer/autumn route. During each crossing, a small motorised model of Queen

Mary would travel along the mural to indicate the vessel's progress en route.

As an alternative to the main

dining room, Queen Mary featured a separate cabin-class Verandah Grill on the

Sun Deck at the upper aft of the ship. The Verandah Grill was an exclusive à la

carte restaurant with a capacity of approximately eighty passengers and was

converted to the Starlight Club at night. Also on board was the Observation

Bar, an Art Deco-styled lounge with wide ocean views. Arthur J. Davis of

Messrs, Mewes and Davis, and Benjamin Wistar Morris designed the Queen Mary's

interior spaces, including the staircases, foyers, and entrances, which were

constructed by H.H. Martyn & Co.

Woods from different regions of

the British Empire were used in her public rooms and staterooms. Accommodation

ranged from fully equipped, luxurious cabin (first) class staterooms to modest

and cramped third-class cabins. Artists commissioned by Cunard in 1933 for

works of art in the interior include Edward Wadsworth and A. Duncan Carse.

In late August 1939, Queen Mary

was on a return run from New York to Southampton. The international situation

led to her being escorted by the battlecruiser HMS Hood. She arrived safely and

set out again for New York on 1 September. By the time she arrived, war had

been declared and she was ordered to remain in port alongside Normandie until

further notice.

In March 1940, Queen Mary and

Normandie were joined in New York by Queen Mary's new running mate Queen

Elizabeth, fresh from her secret voyage from Clydebank. The three largest

liners in the world sat idle for some time until the Allied commanders decided

that all three ships could be used as troopships. Normandie was destroyed by

fire during her troopship conversion. Queen Mary left New York for Sydney,

Australia in March 1940, where she, along with several other liners, was

converted into a troopship to carry Australian and New Zealand soldiers to the

United Kingdom.

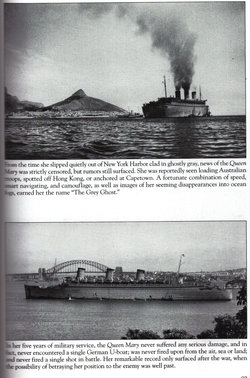

In the conversion, the ship's

hull, superstructure, and funnels were painted navy grey. As a result of her

new colour, and in combination with her great speed, she became known as the

"Grey Ghost". To protect against magnetic mines, a degaussing coil

was fitted around the outside of the hull. Inside, stateroom furniture and

decoration were removed and replaced with triple-tiered (fixed) wooden bunks,

which were later replaced by "standee" (fold-up) bunks.

A total of 6 miles (10 km) of

carpet, 220 cases of china, crystal and silver services, tapestries, and

paintings were removed and stored in warehouses for the duration of the war.

The woodwork in the staterooms, the cabin-class dining room, and other public

areas were covered with leather. Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth were the

largest and fastest troopships involved in the war, often carrying as many as

15,000 men in a single voyage, and often travelling out of convoy and without

escort. Indeed, only a handful of ships, such as the Polish destroyer ORP

Blyskawica, could even provide an escort. The Queens high speed and zigzag

courses made it virtually impossible for U-boats to catch them, although one

attempted to attack the ship. On 25 May 1944, U-853 spotted Queen Mary and

submerged to attack, but the ship outran the U-boat before it could do so.[28]

Because of their importance to the war effort, Adolf Hitler offered a bounty of

1 million Reichsmarks and Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross, Germany's highest

military honor, to any U-boat captain that sank either ship.

The Queen Mary was not so lucky

throughout the war. On 2 October 1942, she accidentally sank one of her escort

ships, slicing through the light cruiser HMS Curacoa off the Irish coast with a

loss of 338 lives. Queen Mary was carrying thousands of Americans of the 29th

Infantry Division[30] to join the Allied forces in Europe.[31] Due to the risk

of U-boat attacks, Queen Mary was under orders not to stop under any

circumstances and steamed onward with a fractured stem. Some sources claim that

hours later, the convoy's lead escort, consisting of Bramham and one other

ship,[32] returned to rescue 99 survivors of Curacoa's crew of 437, including

her captain John W. Boutwood.[33][34][35] This claim is contradicted by the

liner's then Staff Captain Harry Grattidge, who recorded that Queen Mary's

Captain, Gordon Illingsworth, immediately ordered the accompanying destroyers

to look for survivors within moments of Curacoa's sinking.

Later that year, from 8–14

December 1942, Queen Mary carried 10,389 soldiers and 950 crew (total

11,339).[38] During this trip, on 11 December, while 700 miles (1,100 km) from

Scotland during a gale, she was suddenly broadsided on her starboard side by a

rogue wave that might have reached a height of 28 metres (92 ft).[39] An

account of this crossing can be found in Carter's book. As quoted in the book,

Carter's father, Dr. Norval Carter, part of the 110th Station Hospital on board

at the time, wrote in a letter that at one point Queen Mary "damned near

capsized... One moment the top deck was at its usual height and then, swoom!

Down, over, and forward she would pitch." It was calculated later that the

ship rolled 52 degrees, and would have capsized had she rolled another three

degrees.

From 25 to 30 July 1943, Queen

Mary carried 15,740 soldiers and 943 crew (total 16,683),[42] a standing record

for the most passengers ever transported on one vessel. This was only possible

in summer as passengers had to sleep on deck.

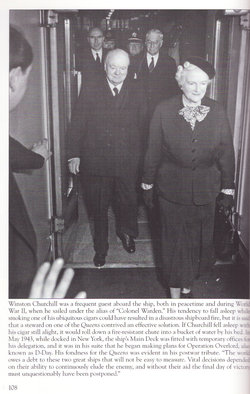

During the war, Queen Mary

carried British Prime Minister Winston Churchill across the Atlantic three

times for meetings with fellow Allied forces officials. He was listed on the

passenger manifests as "Colonel Warden".[45] On one crossing in 1943,

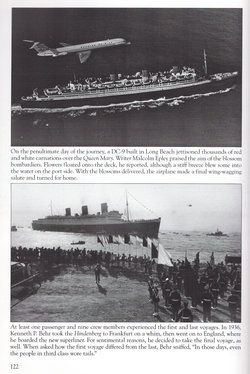

Churchill and his staff planned the Normandy Invasion and he signed the D-Day

Declaration aboard.[46] Churchill later stated that the Queens,

"challenged the fury of Hitlerism in the battle of the Atlantic. Without

their aid, the day of final victory must unquestionably have been postponed.”

By the war's end, Queen Mary had carried over 800,000 troops and traveled over

600,000 miles across the world's oceans.