Shipping from Europe with tracking number

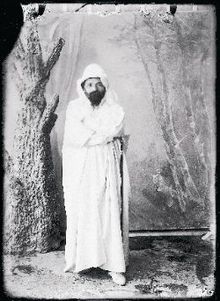

Boris Schatz-Grandma

Boris Schatz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 23, 1866 |

| Died | March 23, 1932 (aged 65) |

Boris Schatz (Hebrew: בוריס שץ; 23 December 1866 – 23 March 1932) was a Lithuanian Jewish artist and sculptor who settled in Israel. Schatz, who became known as the "father of Israeli art," founded the Bezalel School in Jerusalem. After Schatz died, part of his art collection, including a famous self portrait by Dutch Master Jozef Israëls, given to him by the artist, eventually became the nucleus of the Israel Museum.[1]

Biography

Boris Schatz was born in Varniai, in the Kovno Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Lithuania). His father, a teacher in a cheder (a religious school), sent him to study in a yeshiva in Vilnius, Lithuania.[2][3] In 1883, while at the yeshiva, he enrolled at the Vilnius School of Drawing, where he was a student until June 1885. In 1887, he met the Jewish sculptor Mark Antokolsky, who was visiting his parents. He showed Antokolski a small figurine of a Jew in a prayer shawl he had carved from black stone. Antokolsky secured a stipend for Schatz and encouraged him to apply for the St. Petersburg Academy of Art, but the plan to study there did not work out. Meanwhile, he began to teach drawing privately in Vilnius. In 1888, he moved to Warsaw and taught art in Jewish schools. His first sculpture “Hendel,” created in Warsaw, is an ode to the Jewish peddler.[4] In the summer of 1889, Schatz married Eugenia (Genia) Zhirmunsky.[5] In 1889, Schatz moved to Paris with wife to study painting at the Académie Cormon and sculpture under Antokolski. In 1890, they lived in a small French town, Banyuls-sur-Mer, for six months. In 1894 Schatz gained recognition for his sculpture "Mattathias the Maccabee" (present location unknown). At the end of 1895, Schatz moved to Sofia, Bulgaria, at the invitation of Prince Ferdinand I of Bulgaria, where his daughter Angelika was born in 1897. Genia left him for a student of Schatz's, Andrey Nikolov, later a well-known Bulgarian sculptor, and took Angelika with her.[6]

In March 1904, Schatz sailed to the United States to oversee the construction of the Bulgarian Pavilion at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. He remained in the country for ten months, until the end of December 1904. Back in Sofia, he declared himself in love with 16-year-old Theodora (Dora) Gabe, later a renowned Bulgarian poet and children's author. In 1905, heartbroken when she did not return his affection, Schatz left for Berlin, where he stayed with the Zionist illustrator Ephraim Moses Lilien. Lilien introduced him to Franz Oppenheimer, a supporter of cooperative land settlement in Israel, and Otto Warburg, later president of the World Zionist Organization. Both were enthusiastic about his idea of establishing an art school in Jerusalem. The founding of Bezalel was officially proclaimed on October 8, 1905.[7]

In 1911, Schatz married Olga Pevzner, a writer and art history teacher.[8] Their children Zahara Schatz (1916–1999) and Bezalel Schatz (1912–1978), nicknamed Lilik, were also artists.[9] Angelika became a painter, too, gaining recognition in the 1930s in France and Bulgaria. For many years, it was believed the relationship ended when Genia and Boris Schatz divorced. Letters discovered in the Central Zionist Archives reveal that they remained in touch.[10]

The 1955 Israel Prize for Art was awarded to Zahara in recognition of the whole Schatz family.

While living on the shore of the Sea of Galilee during the First World War, Shatz wrote a futurist novel entitled The Rebuilt Jerusalem (Yerushalayim Ha-Benuya) in which Bezalel ben Uri, the Biblical architect of the Mishkan appears at the Bezalel School and takes Schatz on a tour of Israel in the year 2018.[11]

Schatz died while on a fundraising tour in Denver, Colorado in 1932.

Art career

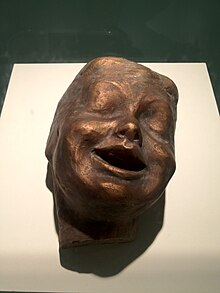

In 1895, Schatz accepted an invitation from Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria to become the official court sculptor and to establish that country's Royal Academy of Art. In 1900, he received a gold medal for his statue, Bust of an Old Woman.

Three years later, in 1903, he met Theodor Herzl and became an ardent Zionist. At the Fifth Zionist Congress of 1905, he proposed creating a Jewish art school. In 1906 he founded an art center in Jerusalem, later named "Bezalel" after Bezalel Ben Uri, the biblical artisan who designed the Tabernacle and its ritual objects. In the following years, Schatz organized exhibitions of his students' work in Europe and the United States; they were the first international exhibitions of Jewish artists from Israel.

Schatz, a fiery visionary, wrote in his will: "To my teachers and assistants at Bezalel I give my final thanks for their hard work in the name of the Bezalel ideal. Moreover, I beg forgiveness from you for the great precision that I sometimes demanded of you and that perhaps caused some resentment ... The trouble was that Bezalel was founded before its time, and the Zionists were not yet capable of understanding it." Schatz's will was publicized for the first time in 2005.[12]

Bezalel art school

Bezalel opened on Ethiopia Street in Jerusalem in 1906. The idea was to support the development of Jewish art and strengthen national pride by engaging in themes relevant to Jewish nationality.[13] The school's stated goals were "to train the people of Jerusalem in crafts, develop original Jewish art and support Jewish artists, and to find visual expression for the much yearned-for national and spiritual independence that seeks to create a synthesis between European artistic traditions and the Jewish design traditions of the East and West, and to integrate it with the local culture of the Land of Israel.” In 1908, the school moved to a permanent home on what became Shmuel Hanagid Street, which allowed more departments to be opened and the scope of activities expanded.[14]

Of the three buildings Schatz purchased from a wealthy Palestinian Arab. one was his personal residence and the other two housed the art school and a national art museum. The school was established based on the Russian concept of an arts and crafts school and workshop. Bezalel's motto was "Art is the bud, craft is the fruit."[15] The school offered instruction in painting and sculpture alongside crafts such as carpet making, metalworking and woodcarving.[16]

In the wake of financial difficulties, the school closed in 1929. Schatz died while fundraising on behalf of the school in the United States. His body was brought back to Jerusalem and buried on the Mount of Olives. Bezalel reopened in 1935 as the New Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts.

Awards and recognition

- 1898 silver medal in Science and Art, Sofia, Bulgaria

- 1900 gold medal for Bust of an Old Woman

- 1900 silver medal at Exposition Internationale, Paris

- 1904 silver medal at 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, Missouri

Naftali Herz Imber

Naftali Herz Imber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Naftali Herz Imber 27 December 1856 |

| Died | 8 October 1909 (aged 52) |

| Resting place | Givat Shaul Cemetery, Jerusalem, Israel 31°47′53.28″N 35°10′39.82″ECoordinates: 31°47′53.28″N 35°10′39.82″E |

| Known for | Hatikvah (The Hope) |

Naftali Herz Imber (Hebrew: נפתלי הרץ אימבר, Yiddish: נפתלי הערץ אימבער; December 27, 1856 – October 8, 1909) was a Jewish Hebrew-language poet, most notable for writing "Hatikvah", the poem that became the basis for the Israeli national anthem.

Biography

Naftali Herz Imber was born in Złoczów (now Zolochiv, Ukraine), a city in Galicia, which then was part of the Austrian Empire.[1] His parents were Joshua Heschel Schorr and Hodel Imber, who followed a strictly Orthodox lifestyle.[2] He began writing poetry at the age of 10 and several years later received an award from Emperor Franz Joseph for a poem on the centenary of Bukovina's joining to the Austrian Empire.[3] His brother, Shmaryahu Imber, also became a writer and a local teacher, and his son, Naftali's nephew Shmuel Yankev, became a Yiddish language poet. In his youth Naftali Herz Imber traveled through Hungary, Serbia, and Romania.

In 1882 Imber moved to Ottoman Palestine as a secretary of Sir Laurence Oliphant. He lived with Oliphant and his wife Alice in their homes in Haifa and Daliyat al-Karmel.[4] Oliphant sent him to Beirut to learn the art of watchmaking. Upon his return he helped Imber open a shop in Haifa. In 1884, he moved to Jerusalem, where he wrote poems suffused with elation and hope. In 1889, after quarreling with Oliphant, Imber departed for England. From there he traveled to Paris, Berlin and Bombay. In 1892, he headed for the United States, traveling from one city to another.[2]

In Chicago he met a Protestant physician, Amanda Katie, who converted to Judaism and married him. Israel Zangwill described her as "a Christian crank." The brief marriage ended in divorce.[5] The eminent Jewish judge, Mayer Sulzberger, became his benefactor, providing him with a monthly allowance that allowed him to survive.[2]

Literary career

In 1882, he published his first book of poems, Morning Star (ברקאי Barkai), in Jerusalem.[6] One of the book's poems was Tikvateinu ("Our Hope"); its very first version was written already in 1877 in Iaşi, Romania. This poem soon became the lyrics of the Zionist anthem and later the Israeli national anthem Hatikvah.

Imber has been described as the "first Hebrew beatnik."[7] He made a mockery of the serious and had a sardonic vulgar wit.[8] Apart from writing his own poems, Imber also translated Omar Khayyam into Hebrew.[9] Additionally, he published Treasures of Two Worlds: Unpublished Legends and Traditions of the Jewish Nation (1910), which posited that the Tabernacle carried by the Hebrews during their 40 years in the desert contained an electrical generator, and that King Solomon invented the telephone.[10]

Imber died penniless in New York City on October 8, 1909 from the effects of chronic alcoholism, nonetheless beloved by the local Jewish community.[5] He had made prior arrangement for his burial by selling a poem, but with his immediate family living in Europe and unavailable to make his funeral arrangements, there was controversy about the cemetery in which he was to be buried.[11] He was buried in Mount Zion Cemetery in Queens,[12] In 1953, he was re-interred at Har HaMenuchot, in Jerusalem.