Shipping from Europe with tracking number $24 /79mm-79mm,315gr,Paris MINT by Grouzat

François-Marie Arouet (French: [fʁɑ̃swa maʁi aʁwɛ]; 21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778), known by his nom de plume Voltaire (/vɒlˈtɛər, voʊlˈ-/;[5][6][7] also US: /vɔːlˈ-/,[8][9] French: [vɔltɛːʁ]), was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher famous for his wit, his criticism of Christianity, especially the Roman Catholic Church, as well as his advocacy of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state.

Voltaire was a versatile and prolific writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, and historical and scientific works. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and more than 2,000 books and pamphlets.[10] He was an outspoken advocate of civil liberties, despite the risk this placed him in under the strict censorship laws of the time. As a satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma, and the French institutions of his day.

Judaism

According to Orthodox rabbi Joseph Telushkin, the most significant Enlightenment hostility against Judaism was found in Voltaire;[148] thirty of the 118 articles in his Dictionnaire philosophique dealt with Jews and described them in consistently negative ways.[149][150] For example, in Voltaire's A Philosophical Dictionary, he wrote of Jews: "In short, we find in them only an ignorant and barbarous people, who have long united the most sordid avarice with the most detestable superstition and the most invincible hatred for every people by whom they are tolerated and enriched."[151]

On the other hand, Peter Gay, a contemporary authority on the Enlightenment,[148] also points to Voltaire's remarks (for instance, that the Jews were more tolerant than the Christians) in the Traité sur la tolérance and surmises that "Voltaire struck at the Jews to strike at Christianity". Whatever anti-semitism Voltaire may have felt, Gay suggests, derived from negative personal experience.[152] Bertram Schwarzbach's far more detailed studies of Voltaire's dealings with Jewish people throughout his life concluded that he was anti-biblical, not anti-semitic. His remarks on the Jews and their "superstitions" were essentially no different from his remarks on Christians.[153]

Telushkin states that Voltaire did not limit his attack to aspects of Judaism that Christianity used as a foundation, repeatedly making it clear that he despised Jews.[148] Arthur Hertzberg claims that Gay's second suggestion is also untenable, as Voltaire himself denied its validity when he remarked that he had "forgotten about much larger bankruptcies through Christians".[clarification needed][154]

Some authors link Voltaire's anti-Judaism to his polygenism. According to Joxe Azurmendi this anti-Judaism has a relative importance in Voltaire's philosophy of history. However, Voltaire's anti-Judaism influences later authors like Ernest Renan.[155]

According to the historian Will Durant, Voltaire had initially condemned the persecution of Jews on several occasions including in his work Henriade.[156] As stated by Durant, Voltaire had praised the simplicity, sobriety, regularity, and industry of Jews. However, subsequently, Voltaire had become strongly anti-Semitic after some regrettable personal financial transactions and quarrels with Jewish financiers. In his Essai sur les moeurs Voltaire had denounced the ancient Hebrews using strong language; a Catholic priest had protested against this censure. The anti-Semitic passages in Voltaire's Dictionnaire philosophique were criticized by Issac Pinto in 1762. Subsequently, Voltaire agreed with the criticism of his anti-Semitic views and stated that he had been "wrong to attribute to a whole nation the vices of some individuals";[157] he also promised to revise the objectionable passages for forthcoming editions of the Dictionnaire philosophique, but failed to do so.[157]

Islam

Voltaire's views about Islam were generally negative, and he found its holy book, the Quran, to be ignorant of the laws of physics.[158] In a 1740 letter to Frederick II of Prussia, Voltaire ascribes to Muhammad a brutality that "is assuredly nothing any man can excuse" and suggests that his following stemmed from superstition; Voltaire continued, "But that a camel-merchant should stir up insurrection in his village; that in league with some miserable followers he persuades them that he talks with the angel Gabriel; that he boasts of having been carried to heaven, where he received in part this unintelligible book, each page of which makes common sense shudder; that, to pay homage to this book, he delivers his country to iron and flame; that he cuts the throats of fathers and kidnaps daughters; that he gives to the defeated the choice of his religion or death: this is assuredly nothing any man can excuse, at least if he was not born a Turk, or if superstition has not extinguished all natural light in him."[159]

In 1748, after having read Henri de Boulainvilliers and George Sale,[160] he wrote again about Mohammed and Islam in "De l'Alcoran et de Mahomet" ("On the Quran and on Mohammed"). In this essay, Voltaire maintained that Mohammed was a "sublime charlatan"[f] Drawing on complementary information in Herbelot's "Oriental Library", Voltaire, according to René Pomeau, adjudged the Quran, with its "contradictions, ... absurdities, ... anachronisms", to be "rhapsody, without connection, without order, and without art".[161][162][163][164] Thus he "henceforward conceded"[164] that "if his book was bad for our times and for us, it was very good for his contemporaries, and his religion even more so. It must be admitted that he removed almost all of Asia from idolatry" and that "it was difficult for such a simple and wise religion, taught by a man who was constantly victorious, could hardly fail to subjugate a portion of the earth." He considered that "its civil laws are good; its dogma is admirable which it has in common with ours" but that "his means are shocking; deception and murder".[165]

In his Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations (published 1756), Voltaire deals with the history of Europe before Charlemagne to the dawn of the age of Louis XIV, and that of the colonies and the East. As a historian, he devoted several chapters to Islam,[166][167][168] Voltaire highlighted the Arabian, Turkish courts, and conducts.[164][169][169][170] Here he called Mohammed a "poet", and stated that he was not an illiterate.[171] As a "legislator", he "changed the face of part of Europe [and] one half of Asia."[172][173][174] In chapter VI, Voltaire finds similarities between Arabs and ancient Hebrews, that they both kept running to battle in the name of God, and sharing a passion for the spoils of war.[175] Voltaire continues that, "It is to be believed that Mohammed, like all enthusiasts, violently struck by his ideas, first presented them in good faith, strengthened them with fantasy, fooled himself in fooling others, and supported through necessary deceptions a doctrine which he considered good."[176][177] He thus compares "the genius of the Arab people" with "the genius of the ancient Romans".[178]

Drama Mahomet

The tragedy Fanaticism, or Mahomet the Prophet (French: Le fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophete) was written in 1736 by Voltaire. The play is a study of religious fanaticism and self-serving manipulation. The character Muhammad orders the murder of his critics.[179] Voltaire described the play as "written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect."[180]

Voltaire described Muhammad as an "impostor", a "false prophet", a "fanatic" and a "hypocrite".[181][182] Defending the play, Voltaire said that he "tried to show in it into what horrible excesses fanaticism, led by an impostor, can plunge weak minds".[183] When Voltaire wrote in 1742 to César de Missy, he described Mohammed as deceitful.[184][185]

In his play, Mohammed was "whatever trickery can invent that is most atrocious and whatever fanaticism can accomplish that is most horrifying. Mahomet here is nothing other than Tartuffe with armies at his command."[186][187] After later having judged that he had made Mohammed in his play "somewhat nastier than he really was",[188] Voltaire claims that Muhammad stole the idea of an angel weighing both men and women from Zoroastrians, who are often referred to as "Magi". Voltaire continues about Islam, saying:

In a 1745 letter recommending the play to Pope Benedict XIV, Voltaire described Muhammad as "the founder of a false and barbarous sect" and "a false prophet". Voltaire wrote: "Your holiness will pardon the liberty taken by one of the lowest of the faithful, though a zealous admirer of virtue, of submitting to the head of the true religion this performance, written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect. To whom could I with more propriety inscribe a satire on the cruelty and errors of a false prophet, than to the vicar and representative of a God of truth and mercy?"[190][191] His view was modified slightly for Essai sur les Moeurs et l'Esprit des Nations, although it remained negative.[132][192][193][194] In 1751, Voltaire performed his play Mohamet once again, with great success.[195]

Hinduism

Commenting on the sacred texts of the Hindus, the Vedas, Voltaire observed:

He regarded Hindus as "a peaceful and innocent people, equally incapable of hurting others or of defending themselves."[197] Voltaire was himself a supporter of animal rights and was a vegetarian.[198] He used the antiquity of Hinduism to land what he saw as a devastating blow to the Bible's claims and acknowledged that the Hindus' treatment of animals showed a shaming alternative to the immorality of European imperialists.[199]

Confucianism

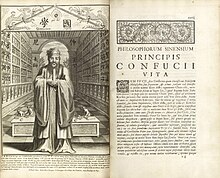

The works of Confucius were translated into European languages through the agency of Jesuit scholars stationed in China.[g] Matteo Ricci was among the earliest to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and father Prospero Intorcetta wrote about the life and works of Confucius in Latin in 1687.[200]

Translations of Confucian texts influenced European thinkers of the period,[201] particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western civilisation.[200][202] Voltaire was also influenced by Confucius, seeing the concept of Confucian rationalism as an alternative to Christian dogma.[203] He praised Confucian ethics and politics, portraying the sociopolitical hierarchy of China as a model for Europe.[203]

With the translation of Confucian texts during the Enlightenment, the concept of a meritocracy reached intellectuals in the West, who saw it as an alternative to the traditional ancient regime of Europe.[204] Voltaire wrote favourably of the idea, claiming that the Chinese had "perfected moral science" and advocating an economic and political system modeled after that of the Chinese.[204]

Views on race and slavery

Voltaire rejected the biblical Adam and Eve story and was a polygenist who speculated that each race had entirely separate origins.[205][206] According to William Cohen, like most other polygenists, Voltaire believed that because of their different origins, blacks did not entirely share the natural humanity of whites.[207] According to David Allen Harvey, Voltaire often invoked racial differences as a means to attack religious orthodoxy, and the Biblical account of creation.[208]

His most famous remark on slavery is found in Candide, where the hero is horrified to learn "at what price we eat sugar in Europe" after coming across a slave in French Guiana who has been mutilated for escaping, who opines that, if all human beings have common origins as the Bible taught, it makes them cousins, concluding that "no one could treat their relatives more horribly". Elsewhere, he wrote caustically about "whites and Christians [who] proceed to purchase negroes cheaply, in order to sell them dear in America". Voltaire has been accused of supporting the slave trade as per a letter attributed to him,[209][210][211] although it has been suggested that this letter is a forgery "since no satisfying source attests to the letter's existence."[212]

In his Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire endorses Montesquieu's criticism of the slave trade: "Montesquieu was almost always in error with the learned, because he was not learned, but he was almost always right against the fanatics and the promoters of slavery."[213]

Zeev Sternhell argues that despite his shortcomings, Voltaire was a forerunner of liberal pluralism in his approach to history and non-European cultures.[214] Voltaire wrote, "We have slandered the Chinese because their metaphysics is not the same as ours ... This great misunderstanding about Chinese rituals has come about because we have judged their usages by ours, for we carry the prejudices of our contentious spirit to the end of the world."[214] In speaking of Persia, he condemned Europe's "ignorant audacity" and "ignorant credulity". When writing about India, he declares, "It is time for us to give up the shameful habit of slandering all sects and insulting all nations!"[214] In Essai sur les mœurs et l'esprit des nations, he defended the integrity of the Native Americans and wrote favorably of the Inca Empire.[215]

Appreciation and influence

According to Victor Hugo: "To name Voltaire is to characterize the entire eighteenth century."[216] Goethe regarded Voltaire to be the greatest literary figure in modern times, and possibly of all times.[217] According to Diderot, Voltaire's influence on posterity would extend far into the future.[218][h] Napoleon commented that till he was sixteen he "would have fought for Rousseau against the friends of Voltaire, today it is the opposite ... The more I read Voltaire the more I love him. He is a man always reasonable, never a charlatan, never a fanatic."[219] Frederick the Great commented on his good fortune for having lived in the age of Voltaire, and corresponded with him throughout his reign until Voltaire's death.[220] In England, Voltaire's views influenced Godwin, Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, Bentham, Byron and Shelley.[217] Macaulay made note of the fear that Voltaire's very name incited in tyrants and fanatics.[221][i]

In Russia, Catherine the Great had been reading Voltaire for sixteen years prior to becoming Empress in 1762.[220][222] In October 1763, she began a correspondence with the philosopher that continued till his death. The content of these letters has been described as being akin to a student writing to a teacher.[223] Upon Voltaire's death, the Empress purchased his library, which was then transported and placed in The Hermitage.[224] Alexander Herzen remarked that "The writings of the egoist Voltaire did more for liberation than those of the loving Rousseau did for brotherhood."[225] In his famous letter to N. V. Gogol, Vissarion Belinsky wrote that Voltaire "stamped out the fires of fanaticism and ignorance in Europe by ridicule."[226]

In his native Paris, Voltaire was viewed as the defender of Jean Calas and Pierre Sirven.[217] Although he failed in securing the annulment of la Barre's execution for "blasphemies" against Christianity, despite a protracted campaign, the criminal code that sanctioned the execution was revised during Voltaire's lifetime.[227] In 1764, Voltaire successfully intervened and secured the release of Claude Chamont for the crime of attending Protestant services. When Comte de Lally was executed for treason in 1766, Voltaire wrote a 300-page document absolving de Lally. Subsequently, in 1778, the judgment against de Lally was expunged just before Voltaire's death. The Genevan Protestant minister Pomaret once said to Voltaire, "You seem to attack Christianity, and yet you do the work of a Christian."[228] Frederick the Great noted the significance of a philosopher capable of influencing judges to change their unjust decisions, commenting that this alone is sufficient to ensure the prominence of Voltaire as a humanitarian.[228]

Under the French Third Republic, anarchists and socialists often invoked Voltaire's writings in their struggles against militarism, nationalism, and the Catholic Church.[229] The section condemning the futility and imbecility of war in the Dictionnaire philosophique was a frequent favorite, as were his arguments that nations can only grow at the expense of others.[230] Following the liberation of France from the Vichy regime in 1944, Voltaire's 250th birthday was celebrated in both France and the Soviet Union, honoring him as "one of the most feared opponents" of the Nazi collaborators and someone "whose name symbolizes freedom of thought, and hatred of prejudice, superstition, and injustice."[231]

Jorge Luis Borges stated that "not to admire Voltaire is one of the many forms of stupidity" and included his short fiction such as Micromégas in "The Library of Babel" and "A Personal Library."[232] Gustave Flaubert believed that France had erred gravely by not following the path forged by Voltaire instead of Rousseau.[233] Most architects of modern America were adherents of Voltaire's views.[217] According to Will Durant: