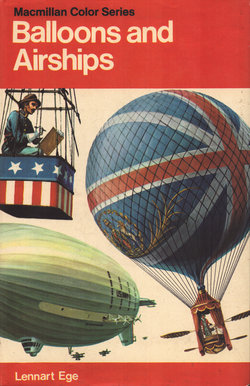

BALLOONS

AND AIRSHIPS HBDJ MONTGOLFIER ZEPPELIN US NAVY SANTOS-DUMONT R34 NORGE PARSEVAL

MAYFLY SCHUTTE-LANZ CAQUOT BLIMPS WW1 WW2 BARRAGE AKRON MACON SHENANDOAH LOS

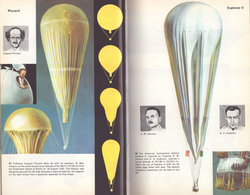

ANGELES GRAF ZEPPELIN HINDENBERG GOODYEAR ZRS R100 R101 PICCARD EXPLORER ZPN

K-CLASS WW JAPANESE FU-GO WEAPON ZSG

MACMILLAN COLOR SERIES HARDBOUND

BOOK with DUSTJACKET in ENGLISH by LENNART EGE

A PICTORIAL HIGHTORY OF

LIGHTER-THAN-AIR FLIGHT LTA

---------------------------

Additional Information from Internet

Encyclopedia

In 1670, the Jesuit Father

Francesco Lana de Terzi, sometimes referred to as the "Father of

Aeronautics", published a description of an "Aerial Ship"

supported by four copper spheres from which the air was evacuated. Although the

basic principle is sound, such a craft was unrealizable then and remains so to

the present day, since external air pressure would cause the spheres to

collapse unless their thickness was such as to make them too heavy to be

buoyant. A hypothetical craft constructed using this principle is known as a

vacuum airship.

In 1709, the

Brazilian-Portuguese Jesuit priest Bartolomeu de Gusmão made a hot air balloon,

the Passarola, ascend to the skies, before an astonished Portuguese court. It

would have been on August 8, 1709, when Father Bartolomeu de Gusmão held, in

the courtyard of the Casa da Índia, in the city of Lisbon, the first Passarola

demonstration.[49][50] The balloon caught fire without leaving the ground, but,

in a second demonstration, it rose to 95 meters in height. It was a small

balloon of thick brown paper, filled with hot air, produced by the "fire

of material contained in a clay bowl embedded in the base of a waxed wooden

tray". The event was witnessed by King John V of Portugal and the future

Pope Innocent XIII.

A more practical dirigible

airship was described by Lieutenant Jean Baptiste Marie Meusnier in a paper

entitled "Mémoire sur l'équilibre des machines aérostatiques"

(Memorandum on the equilibrium of aerostatic machines) presented to the French Academy

on 3 December 1783. The 16 water-color drawings published the following year

depict a 260-foot-long (79 m) streamlined envelope with internal ballonets that

could be used for regulating lift: this was attached to a long carriage that

could be used as a boat if the vehicle was forced to land in water. The airship

was designed to be driven by three propellers and steered with a sail-like aft

rudder. In 1784, Jean-Pierre Blanchard fitted a hand-powered propeller to a

balloon, the first recorded means of propulsion carried aloft. In 1785, he

crossed the English Channel in a balloon equipped with flapping wings for

propulsion and a birdlike tail for steering.

19th century

The 19th century saw continued

attempts to add methods of propulsion to balloons. The Australian William Bland

sent designs for his "Atmotic airship" to the Great Exhibition held

in London in 1851, where a model was displayed. This was an elongated balloon

with a steam engine driving twin propellers suspended underneath. The lift of

the balloon was estimated as 5 tons and the car with the fuel as weighing 3.5

tons, giving a payload of 1.5 tons.[53][54] Bland believed that the machine

could be driven at 80 km/h (50 mph) and could fly from Sydney to London in less

than a week.

In 1852, Henri Giffard became

the first person to make an engine-powered flight when he flew 27 km (17 mi) in

a steam-powered airship. Airships would develop considerably over the next two

decades. In 1863, Solomon Andrews flew his aereon design, an unpowered,

controllable dirigible in Perth Amboy, New Jersey and offered the device to the

U.S. Military during the Civil War. He flew a later design in 1866 around New

York City and as far as Oyster Bay, New York. This concept used changes in lift

to provide propulsive force, and did not need a powerplant. In 1872, the French

naval architect Dupuy de Lome launched a large navigable balloon, which was

driven by a large propeller turned by eight men. It was developed during the

Franco-Prussian war and was intended as an improvement to the balloons used for

communications between Paris and the countryside during the siege of Paris, but

was completed only after the end of the war.

In 1872, Paul Haenlein flew an

airship with an internal combustion engine running on the coal gas used to

inflate the envelope, the first use of such an engine to power an

aircraft.[58][59] Charles F. Ritchel made a public demonstration flight in 1878

of his hand-powered one-man rigid airship, and went on to build and sell five

of his aircraft.

In 1874, Micajah Clark Dyer

filed U.S. Patent 154,654 "Apparatus for Navigating the Air". It is

believed successful trial flights were made between 1872 and 1874, but detailed

dates are not available. The apparatus used a combination of wings and paddle

wheels for navigation and propulsion.

In operating the machinery the

wings receive an upward and downward motion, in the manner of the wings of a

bird, the outer ends yielding as they are raised, but opening out and then

remaining rigid while being depressed. The wings, if desired, may be set at an

angle so as to propel forward as well as to raise the machine in the air. The

paddle-wheels are intended to be used for propelling the machine, in the same

way that a vessel is propelled in water. An instrument answering to a rudder is

attached for guiding the machine. A balloon is to be used for elevating the

flying ship, after which it is to be guided and controlled at the pleasure of

its occupants.

In 1883, the first

electric-powered flight was made by Gaston Tissandier, who fitted a 1.5 hp (1.1

kW) Siemens electric motor to an airship.

The first fully controllable

free flight was made in 1884 by Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs in

the French Army airship La France. La France made the first flight of an

airship that landed where it took off; the 170 ft (52 m) long, 66,000 cu ft

(1,900 m3) airship covered 8 km (5.0 mi) in 23 minutes with the aid of an 8.5

hp (6.3 kW) electric motor,[66] and a 435 kg (959 lb) battery. It made seven

flights in 1884 and 1885.

In 1888, the design of the

Campbell Air Ship, designed by Professor Peter C. Campbell, was built by the

Novelty Air Ship Company. It was lost at sea in 1889 while being flown by

Professor Hogan during an exhibition flight.

From 1888 to 1897, Friedrich

Wölfert built three airships powered by Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft-built

petrol engines, the last of which caught fire in flight and killed both

occupants in 1897.[68] The 1888 version used a 2 hp (1.5 kW) single cylinder Daimler

engine and flew 10 km (6 mi) from Canstatt to Kornwestheim.

In 1897, an airship with an

aluminum envelope was built by the Hungarian-Croatian engineer David Schwarz.

It made its first flight at Tempelhof field in Berlin after Schwarz had died.

His widow, Melanie Schwarz, was paid 15,000 marks by Count Ferdinand von

Zeppelin to release the industrialist Carl Berg from his exclusive contract to

supply Schwartz with aluminium.

From 1897 to 1899, Konstantin

Danilewsky, medical doctor and inventor from Kharkiv (now Ukraine, then Russian

Empire), built four muscle-powered airships, of gas volume 150–180 m3

(5,300–6,400 cu ft). About 200 ascents were made within a framework of experimental

flight program, at two locations, with no significant incidents.

Early 20th century

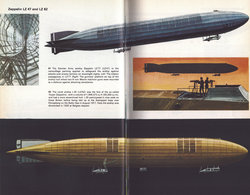

In July 1900, the Luftschiff

Zeppelin LZ1 made its first flight. This led to the most successful airships of

all time: the Zeppelins, named after Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin who began

working on rigid airship designs in the 1890s, leading to the flawed LZ1 in

1900 and the more successful LZ2 in 1906. The Zeppelin airships had a framework

composed of triangular lattice girders covered with fabric that contained

separate gas cells. At first multiplane tail surfaces were used for control and

stability: later designs had simpler cruciform tail surfaces. The engines and

crew were accommodated in "gondolas" hung beneath the hull driving

propellers attached to the sides of the frame by means of long drive shafts.

Additionally, there was a passenger compartment (later a bomb bay) located

halfway between the two engine compartments.

Alberto Santos-Dumont was a

wealthy young Brazilian who lived in France and had a passion for flying. He

designed 18 balloons and dirigibles before turning his attention to

fixed-winged aircraft.[74] On 19 October 1901 he flew his airship Number 6,

from the Parc Saint Cloud to and around the Eiffel Tower and back in under

thirty minutes.[75] This feat earned him the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize of

100,000 francs. Many inventors were inspired by Santos-Dumont's small airships.

Many airship pioneers, such as the American Thomas Scott Baldwin, financed

their activities through passenger flights and public demonstration flights.

Stanley Spencer built the first British airship with funds from advertising

baby food on the sides of the envelope. Others, such as Walter Wellman and

Melvin Vaniman, set their sights on loftier goals, attempting two polar flights

in 1907 and 1909, and two trans-Atlantic flights in 1910 and 1912.

In 1902 the Spanish engineer

Leonardo Torres Quevedo published details of an innovative airship design in

Spain and France titled "Perfectionnements aux aerostats dirigibles"

("Improvements in dirigible aerostats"). With a non-rigid body and

internal bracing wires, it overcame the flaws of these types of aircraft as

regards both rigid structure (zeppelin type) and flexibility, providing the

airships with more stability during flight, and the capability of using heavier

engines and a greater passenger load. A system called "auto-rigid".

In 1905, helped by Captain A. Kindelán, he built the airship "Torres

Quevedo" at the Guadalajara military base.[80] In 1909 he patented an

improved design that he offered to the French Astra company, who started

mass-producing it in 1911 as the Astra-Torres airship.[81] This type of

envelope was employed in the United Kingdom in the Coastal, C Star, and North

Sea airships.[82] The distinctive three-lobed design was widely used during the

Great War by the Entente powers for diverse tasks, principally convoy

protection and anti-submarine warfare. The success during the war even drew the

attention of the Imperial Japanese Navy, who acquired a model in 1922.[83]

Torres also drew up designs of a 'docking station' and made alterations to

airship designs, to find a resolution to the slew of problems faced by airship

engineers to dock dirigibles. In 1910, he proposed the idea of attaching an

airships nose to a mooring mast and allowing the airship to weathervane with

changes of wind direction. The use of a metal column erected on the ground, the

top of which the bow or stem would be directly attached to (by a cable) would

allow a dirigible to be moored at any time, in the open, regardless of wind speeds.

Additionally, Torres' design called for the improvement and accessibility of

temporary landing sites, where airships were to be moored for the purpose of

disembarkation of passengers. The final patent was presented in February 1911

in Belgium, and later to France and the United Kingdom in 1912, under the title

"Improvements in Mooring Arrengements for Airships".

Other airship builders were also

active before the war: from 1902 the French company Lebaudy Frères specialized

in semirigid airships such as the Patrie and the République, designed by their

engineer Henri Julliot, who later worked for the American company Goodrich; the

German firm Schütte-Lanz built the wooden-framed SL series from 1911,

introducing important technical innovations; another German firm

Luft-Fahrzeug-Gesellschaft built the Parseval-Luftschiff (PL) series from

1909,[87] and Italian Enrico Forlanini's firm had built and flown the first two

Forlanini airships.

On May 12, 1902, the inventor

and Brazilian aeronaut Augusto Severo de Albuquerque Maranhao and his French

mechanic, Georges Saché, died when they were flying over Paris in the airship

called Pax. A marble plaque at number 81 of the Avenue du Maine in Paris,

commemorates the location of Augusto Severo accident.[89][90] The Catastrophe

of the Balloon "Le Pax" is a 1902 short silent film recreation of the

catastrophe, directed by Georges Méliès.

In Britain, the Army built their

first dirigible, the Nulli Secundus, in 1907. The Navy ordered the construction

of an experimental rigid in 1908. Officially known as His Majesty's Airship No.

1 and nicknamed the Mayfly, it broke its back in 1911 before making a single

flight. Work on a successor did not start until 1913.

German airship passenger service

known as DELAG (Deutsche-Luftschiffahrts AG) was established in 1910.

In 1910 Walter Wellman

unsuccessfully attempted an aerial crossing of the Atlantic Ocean in the

airship America.

World War I

The prospect of airships as

bombers had been recognized in Europe well before the airships were up to the

task. H. G. Wells' The War in the Air (1908) described the obliteration of

entire fleets and cities by airship attack. The Italian forces became the first

to use dirigibles for a military purpose during the Italo–Turkish War, the

first bombing mission being flown on 10 March 1912. World War I marked the

airship's real debut as a weapon. The Germans, French, and Italians all used

airships for scouting and tactical bombing roles early in the war, and all

learned that the airship was too vulnerable for operations over the front. The

decision to end operations in direct support of armies was made by all in 1917.

Many in the German military

believed they had found the ideal weapon with which to counteract British naval

superiority and strike at Britain itself, while more realistic airship

advocates believed the zeppelin's value was as a long range scout/attack craft

for naval operations. Raids on England began in January 1915 and peaked in

1916: following losses to the British defenses only a few raids were made in

1917–18, the last in August 1918.[94] Zeppelins proved to be terrifying but

inaccurate weapons. Navigation, target selection and bomb-aiming proved to be

difficult under the best of conditions, and the cloud cover that was frequently

encountered by the airships reduced accuracy even further. The physical damage

done by airships over the course of the war was insignificant, and the deaths

that they caused amounted to a few hundred.[95] Nevertheless, the raid caused a

significant diversion of British resources to defense efforts. The airships

were initially immune to attack by aircraft and anti-aircraft guns: as the

pressure in their envelopes was only just higher than ambient air, holes had

little effect. But following the introduction of a combination of incendiary

and explosive ammunition in 1916, their flammable hydrogen lifting gas made

them vulnerable to the defending aeroplanes. Several were shot down in flames

by British defenders, and many others destroyed in accidents. New designs

capable of reaching greater altitude were developed, but although this made

them immune from attack it made their bombing accuracy even worse.

Countermeasures by the British

included sound detection equipment, searchlights and anti-aircraft artillery,

followed by night fighters in 1915. One tactic used early in the war, when

their limited range meant the airships had to fly from forward bases and the

only zeppelin production facilities were in Friedrichshafen, was the bombing of

airship sheds by the British Royal Naval Air Service. Later in the war, the

development of the aircraft carrier led to the first successful carrier-based

air strike in history: on the morning of 19 July 1918, seven Sopwith 2F.1

Camels were launched from HMS Furious and struck the airship base at Tønder,

destroying zeppelins L 54 and L 60.

The British Army had abandoned

airship development in favour of aeroplanes before the start of the war, but

the Royal Navy had recognized the need for small airships to counteract the

submarine and mine threat in coastal waters.[97] Beginning in February 1915,

they began to develop the SS (Sea Scout) class of blimp. These had a small

envelope of 1,699–1,982 m3 (60,000–70,000 cu ft) and at first used aircraft

fuselages without the wing and tail surfaces as control cars. Later, more

advanced blimps with purpose-built gondolas were used. The NS class (North Sea)

were the largest and most effective non-rigid airships in British service, with

a gas capacity of 10,200 m3 (360,000 cu ft), a crew of 10 and an endurance of

24 hours. Six 230 lb (100 kg) bombs were carried, as well as three to five

machine guns. British blimps were used for scouting, mine clearance, and convoy

patrol duties. During the war, the British operated over 200 non-rigid

airships.[98] Several were sold to Russia, France, the United States, and Italy.

The large number of trained crews, low attrition rate and constant

experimentation in handling techniques meant that at the war's end Britain was

the world leader in non-rigid airship technology.

The Royal Navy continued

development of rigid airships until the end of the war. Eight rigid airships

had been completed by the armistice, (No. 9r, four 23 Class, two R23X Class and

one R31 Class), although several more were in an advanced state of completion

by the war's end.[99] Both France and Italy continued to use airships

throughout the war. France preferred the non-rigid type, whereas Italy flew 49

semi-rigid airships in both the scouting and bombing roles.

Aeroplanes had almost entirely

replaced airships as bombers by the end of the war, and Germany's remaining

zeppelins were destroyed by their crews, scrapped or handed over to the Allied

powers as war reparations. The British rigid airship program, which had mainly

been a reaction to the potential threat of the German airships, was wound down.

The interwar period

Britain, the United States and

Germany built rigid airships between the two world wars. Italy and France made

limited use of Zeppelins handed over as war reparations. Italy, the Soviet

Union, the United States and Japan mainly operated semi-rigid airships.

Under the terms of the Treaty of

Versailles, Germany was not allowed to build airships of greater capacity than

a million cubic feet. Two small passenger airships, LZ 120 Bodensee and its

sister ship LZ 121 Nordstern, were built immediately after the war but were

confiscated following the sabotage of the wartime Zeppelins that were to have

been handed over as war reparations: Bodensee was given to Italy and Nordstern

to France. On May 12, 1926, the Italian built semi-rigid airship Norge was the

first aircraft to fly over the North Pole.

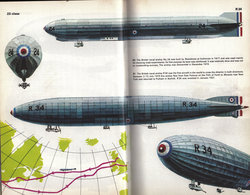

The British R33 and R34 were

near-identical copies of the German L 33, which had come down almost intact in

Yorkshire on 24 September 1916.[101] Despite being almost three years out of

date by the time they were launched in 1919, they became two of the most

successful airships in British service. The creation of the Royal Air Force

(RAF) in early 1918 created a hybrid British airship program. The RAF was not

interested in airships while the Admiralty was, so a deal was made where the

Admiralty would design any future military airships and the RAF would handle

manpower, facilities and operations.[102] On 2 July 1919, R34 began the first

double crossing of the Atlantic by an aircraft. It landed at Mineola, Long

Island on 6 July after 108 hours in the air; the return crossing began on 8

July and took 75 hours. This feat failed to generate enthusiasm for continued

airship development, and the British airship program was rapidly wound down.

During World War I, the U.S.

Navy acquired its first airship, the DH-1,[103] but it was destroyed while

being inflated shortly after delivery to the Navy. After the war, the U.S. Navy

contracted to buy the R 38, which was being built in Britain, but before it was

handed over it was destroyed because of a structural failure during a test

flight.

America then started

constructing the USS Shenandoah, designed by the Bureau of Aeronautics and

based on the Zeppelin L 49.[105] Assembled in Hangar No. 1 and first flown on 4

September 1923[106] at Lakehurst, New Jersey, it was the first airship to be inflated

with the noble gas helium, which was then so scarce that the Shenandoah

contained most of the world's supply. A second airship, USS Los Angeles, was

built by the Zeppelin company as compensation for the airships that should have

been handed over as war reparations according to the terms of the Versailles

Treaty but had been sabotaged by their crews. This construction order saved the

Zeppelin works from the threat of closure. The success of the Los Angeles,

which was flown successfully for eight years, encouraged the U.S. Navy to

invest in its own, larger airships. When the Los Angeles was delivered, the two

airships had to share the limited supply of helium, and thus alternated

operating and overhauls.

In 1922, Sir Dennistoun Burney

suggested a plan for a subsidised air service throughout the British Empire

using airships (the Burney Scheme).[102] Following the coming to power of

Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government in 1924, the scheme was transformed into

the Imperial Airship Scheme, under which two airships were built, one by a

private company and the other by the Royal Airship Works under Air Ministry

control. The two designs were radically different. The "capitalist"

ship, the R100, was more conventional, while the "socialist" ship,

the R101, had many innovative design features. Construction of both took longer

than expected, and the airships did not fly until 1929. Neither airship was

capable of the service intended, though the R100 did complete a proving flight

to Canada and back in 1930.[108] On 5 October 1930, the R101, which had not

been thoroughly tested after major modifications, crashed on its maiden voyage

to India at Beauvais in France killing 48 of the 54 people aboard. Among the

dead were the craft's chief designer and the Secretary of State for Air. The

disaster ended British interest in airships.

The Locarno Treaties of 1925

lifted the restrictions on German airship construction, and the Zeppelin

company started construction of the Graf Zeppelin (LZ 127), the largest airship

that could be built in the company's existing shed, and intended to stimulate

interest in passenger airships. The Graf Zeppelin burned blau gas, similar to

propane, stored in large gas bags below the hydrogen cells, as fuel. Since its

density was similar to that of air, it avoided the weight change as fuel was

used, and thus the need to valve hydrogen. The Graf Zeppelin had an impressive

safety record, flying over 1,600,000 km (990,000 mi) (including the first

circumnavigation of the globe by airship) without a single passenger injury.

The U.S. Navy experimented with

the use of airships as airborne aircraft carriers, developing an idea pioneered

by the British. The USS Los Angeles was used for initial experiments, and the

USS Akron and Macon, the world's largest at the time, were used to test the

principle in naval operations. Each carried four F9C Sparrowhawk fighters in

its hangar, and could carry a fifth on the trapeze. The idea had mixed results.

By the time the Navy started to develop a sound doctrine for using the ZRS-type

airships, the last of the two built, USS Macon, had been wrecked. Meanwhile,

the seaplane had become more capable, and was considered a better investment.

Eventually, the U.S. Navy lost

all three U.S.-built rigid airships to accidents. USS Shenandoah flew into a

severe thunderstorm over Noble County, Ohio while on a poorly planned publicity

flight on 3 September 1925. It broke into pieces, killing 14 of its crew. USS

Akron was caught in a severe storm and flown into the surface of the sea off

the shore of New Jersey on 3 April 1933. It carried no life boats and few life

vests, so 73 of its crew of 76 died from drowning or hypothermia. USS Macon was

lost after suffering a structural failure offshore near Point Sur Lighthouse on

12 February 1935. The failure caused a loss of gas, which was made much worse

when the aircraft was driven over pressure height causing it to lose too much

helium to maintain flight.[111] Only two of its crew of 83 died in the crash

thanks to the inclusion of life jackets and inflatable rafts after the Akron

disaster.

The Empire State Building was

completed in 1931 with a dirigible mast, in anticipation of future passenger

airship service, but no airship ever used the mast. Various entrepreneurs

experimented with commuting and shipping freight via airship.

In the 1930s, the German

Zeppelins successfully competed with other means of transport. They could carry

significantly more passengers than other contemporary aircraft while providing

amenities similar to those on ocean liners, such as private cabins, observation

decks, and dining rooms. Less importantly, the technology was potentially more

energy-efficient than heavier-than-air designs. Zeppelins were also faster than

ocean liners. On the other hand, operating airships was quite involved. Often

the crew would outnumber passengers, and on the ground large teams were

necessary to assist mooring and very large hangars were required at airports.

By the mid-1930s, only Germany

still pursued airship development. The Zeppelin company continued to operate

the Graf Zeppelin on passenger service between Frankfurt and Recife in Brazil,

taking 68 hours. Even with the small Graf Zeppelin, the operation was almost

profitable.[113] In the mid-1930s, work began on an airship designed

specifically to operate a passenger service across the Atlantic.[114] The

Hindenburg (LZ 129) completed a successful 1936 season, carrying passengers

between Lakehurst, New Jersey and Germany. The year 1937 started with the most

spectacular and widely remembered airship accident. Approaching the Lakehurst

mooring mast minutes before landing on 6 May 1937, the Hindenburg suddenly

burst into flames and crashed to the ground. Of the 97 people aboard, 35 died:

13 passengers, 22 aircrew, along with one American ground-crewman. The disaster

happened before a large crowd, was filmed and a radio news reporter was

recording the arrival. This was a disaster that theater goers could see and hear

in newsreels. The Hindenburg disaster shattered public confidence in airships,

and brought a definitive end to their "golden age". The day after the

Hindenburg disaster, the Graf Zeppelin landed safely in Germany after its

return flight from Brazil. This was the last international passenger airship

flight.

Hindenburg's identical sister

ship, the Graf Zeppelin II (LZ 130), could not carry commercial passengers

without helium, which the United States refused to sell to Germany. The Graf

Zeppelin made several test flights and conducted some electronic espionage

until 1939 when it was grounded due to the beginning of the war. The two Graf

Zeppelins were scrapped in April, 1940.

Development of airships

continued only in the United States, and to a lesser extent, the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union had several semi-rigid and non-rigid airships. The semi-rigid

dirigible SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM was among the largest of these craft, and it set

the longest endurance flight at the time of over 130 hours. It crashed into a

mountain in 1938, killing 13 of the 19 people on board. While this was a severe

blow to the Soviet airship program, they continued to operate non-rigid

airships until 1950.

World War II

While Germany determined that

airships were obsolete for military purposes in the coming war and concentrated

on the development of aeroplanes, the United States pursued a program of

military airship construction even though it had not developed a clear military

doctrine for airship use. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December

1941, bringing the United States into World War II, the U.S. Navy had 10

nonrigid airships:

4 K-class: K-2, K-3, K-4 and K-5

designed as patrol ships, all built in 1938.

3 L-class: L-1, L-2 and L-3 as

small training ships, produced in 1938.

1 G-class, built in 1936 for

training.

2 TC-class that were older

patrol airships designed for land forces, built in 1933. The U.S. Navy acquired

both from the United States Army in 1938.

Only K- and TC-class airships

were suitable for combat and they were quickly pressed into service against

Japanese and German submarines, which were then sinking American shipping

within visual range of the American coast. U.S. Navy command, remembering airship's

anti-submarine success in World War I, immediately requested new modern

antisubmarine airships and on 2 January 1942 formed the ZP-12 patrol unit based

in Lakehurst from the four K airships. The ZP-32 patrol unit was formed from

two TC and two L airships a month later, based at NAS Moffett Field in

Sunnyvale, California. An airship training base was created there as well. The

status of submarine-hunting Goodyear airships in the early days of World War II

has created significant confusion. Although various accounts refer to airships

Resolute and Volunteer as operating as "privateers" under a Letter of

Marque, Congress never authorized a commission, nor did the President sign one.

In the years 1942–44,

approximately 1,400 airship pilots and 3,000 support crew members were trained

in the military airship crew training program and the airship military

personnel grew from 430 to 12,400. The U.S. airships were produced by the

Goodyear factory in Akron, Ohio. From 1942 till 1945, 154 airships were built

for the U.S. Navy (133 K-class, 10 L-class, seven G-class, four M-class) and

five L-class for civilian customers (serial numbers L-4 to L-8).

The primary airship tasks were

patrol and convoy escort near the American coastline. They also served as an

organization centre for the convoys to direct ship movements, and were used in

naval search and rescue operations. Rarer duties of the airships included

aerophoto reconnaissance, naval mine-laying and mine-sweeping, parachute unit

transport and deployment, cargo and personnel transportation. They were deemed

quite successful in their duties with the highest combat readiness factor in

the entire U.S. air force (87%).

During the war, some 532 ships

without airship escort were sunk near the U.S. coast by enemy submarines. Only

one ship, the tanker Persephone, of the 89,000 or so in convoys escorted by

blimps was sunk by the enemy. Airships engaged submarines with depth charges

and, less frequently, with other on-board weapons. They were excellent at

driving submarines down, where their limited speed and range prevented them

from attacking convoys. The weapons available to airships were so limited that

until the advent of the homing torpedo they had little chance of sinking a

submarine.

Only one airship was ever

destroyed by U-boat: on the night of 18/19 July 1943, the K-74 from ZP-21

division was patrolling the coastline near Florida. Using radar, the airship

located a surfaced German submarine. The K-74 made her attack run but the U-boat

opened fire first. K-74's depth charges did not release as she crossed the

U-boat and the K-74 received serious damage, losing gas pressure and an engine

but landing in the water without loss of life. The crew was rescued by patrol

boats in the morning, but one crewman, Aviation Machinist's Mate Second Class

Isadore Stessel, died from a shark attack. The U-boat, submarine U-134, was

slightly damaged and the next day or so was attacked by aircraft, sustaining

damage that forced it to return to base. It was finally sunk on 24 August 1943

by a British Vickers Wellington near Vigo, Spain.

Fleet Airship Wing One operated

from Lakehurst, New Jersey, Glynco, Georgia, Weeksville, North Carolina, South

Weymouth NAS Massachusetts, Brunswick NAS and Bar Harbor Maine, Yarmouth, Nova

Scotia, and Argentia, Newfoundland.

K-class blimps of USN Blimp

Squadron ZP-14 conducted antisubmarine warfare operations at the Strait of

Gibraltar in 1944–45.

Some Navy blimps saw action in

the European war theater. In 1944–45, the U.S. Navy moved an entire squadron of

eight Goodyear K class blimps (K-89, K-101, K-109, K-112, K-114, K-123, K-130,

& K-134) with flight and maintenance crews from Weeksville Naval Air

Station in North Carolina to Naval Air Station Port Lyautey, French Morocco.

Their mission was to locate and destroy German U-boats in the relatively

shallow waters around the Strait of Gibraltar where magnetic anomaly detection

(MAD) was viable. PBY aircraft had been searching these waters but MAD required

low altitude flying that was dangerous at night for these aircraft. The blimps

were considered a perfect solution to establish a 24/7 MAD barrier (fence) at

the Straits of Gibraltar with the PBYs flying the day shift and the blimps

flying the night shift. The first two blimps (K-123 & K-130) left South

Weymouth NAS on 28 May 1944 and flew to Argentia, Newfoundland, the Azores, and

finally to Port Lyautey where they completed the first transatlantic crossing

by nonrigid airships on 1 June 1944. The blimps of USN Blimp Squadron ZP-14

(Blimpron 14, aka The Africa Squadron) also conducted mine-spotting and

mine-sweeping operations in key Mediterranean ports and various escorts

including the convoy carrying United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the Yalta Conference in 1945.

Airships from the ZP-12 unit took part in the sinking of the last U-boat before

German capitulation, sinking the U-881 on 6 May 1945 together with destroyers

USS Atherton and USS Moberly.

Other airships patrolled the

Caribbean, Fleet Airship Wing Two, Headquartered at Naval Air Station Richmond,

covered the Gulf of Mexico from Richmond and Key West, Florida, Houma,

Louisiana, as well as Hitchcock and Brownsville, Texas. FAW 2 also patrolled

the northern Caribbean from San Julian, the Isle of Pines (now called Isla de

la Juventud) and Guantánamo Bay, Cuba as well as Vernam Field, Jamaica.

Navy blimps of Fleet Airship

Wing Five, (ZP-51) operated from bases in Trinidad, British Guiana and

Paramaribo, Suriname. Fleet Airship Wing Four operated along the coast of

Brazil. Two squadrons, VP-41 and VP-42 flew from bases at Amapá, Igarapé-Açu,

São Luís Fortaleza, Fernando de Noronha, Recife, Maceió, Ipitanga (near

Salvador, Bahia), Caravelas, Vitória and the hangar built for the Graf Zeppelin

at Santa Cruz, Rio de Janeiro.

Fleet Airship Wing Three

operated squadrons, ZP-32 from Moffett Field, ZP-31 at NAS Santa Ana, and ZP-33

at NAS Tillamook, Oregon. Auxiliary fields were at Del Mar, Lompoc, Watsonville

and Eureka, California, North Bend and Astoria, Oregon, as well as Shelton and

Quillayute in Washington.

From 2 January 1942 until the

end of war airship operations in the Atlantic, the blimps of the Atlantic fleet

made 37,554 flights and flew 378,237 hours. Of the over 70,000 ships in convoys

protected by blimps, only one was sunk by a submarine while under blimp escort.

The Soviet Union flew a single

airship during the war. The W-12, built in 1939, entered service in 1942 for

paratrooper training and equipment transport. It made 1432 flights with 300

metric tons of cargo until 1945. On 1 February 1945, the Soviets constructed a

second airship, a Pobeda-class (Victory-class) unit (used for mine-sweeping and

wreckage clearing in the Black Sea) that crashed on 21 January 1947. Another

W-class – W-12bis Patriot – was commissioned in 1947 and was mostly used until

the mid-1950s for crew training, parades and propaganda.