UNDER

THE SIDEWALKS OF NEW YORK THE SUBWAY SYSTEM HISTORY TRAINS STATIONS

INTERBOROUGH

SOFTBOUND BOOK in ENGLISH by BRIAN

J. CUDAHY 2ND REVISED EDITION

---------------------------

Additional Information from Internet

Encyclopedia

The New York City Subway is a

rapid transit system in the New York City boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn,

Queens, and the Bronx. It is owned by the government of New York City and

leased to the New York City Transit Authority, an affiliate agency of the

state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Opened on October 27,

1904, the New York City Subway is one of the world's oldest public transit

systems, one of the most-used, and the one with the most stations, with 472

stations in operation (423, if stations connected by transfers are counted as

single stations).

The system has operated 24/7

service every day of the year throughout most of its history, barring

emergencies and disasters. By annual ridership, the New York City Subway is the

busiest rapid transit system in both the Western Hemisphere and the Western

world, as well as the eleventh-busiest rapid transit rail system in the

world.[18] The subway carried 2,027,286,000 riders in 2023. On October 29,

2015, more than 6.2 million people rode the subway system, establishing the

highest single-day ridership since ridership was regularly monitored in 1985.

The system is also one of the

world's longest. Overall, the system contains 248 miles (399 km) of routes,[10]

translating into 665 miles (1,070 km) of revenue track[10] and a total of 850

miles (1,370 km) including non-revenue trackage.[11] Of the system's 28 routes

or "services" (which usually share track or "lines" with

other services), 25 pass through Manhattan, the exceptions being the G train,

the Franklin Avenue Shuttle, and the Rockaway Park Shuttle. Large portions of

the subway outside Manhattan are elevated, on embankments, or in open cuts, and

a few stretches of track run at ground level; 40% of track is above ground.[21]

Many lines and stations have both express and local services. These lines have

three or four tracks. Normally, the outer two are used by local trains, while

the inner one or two are used by express trains.

As of 2018, the New York City

Subway's budgetary burden for expenditures was $8.7 billion, supported by

collection of fares, bridge tolls, and earmarked regional taxes and fees, as

well as direct funding from state and local governments.

History

Alfred Ely Beach built the first

demonstration for an underground transit system in New York City in 1869 and

opened it in February 1870. His Beach Pneumatic Transit only extended 312 feet

(95 m) under Broadway in Lower Manhattan operating from Warren Street to Murray

Street[23] and exhibited his idea for an atmospheric railway as a subway. The

tunnel was never extended for political and financial reasons.[25] Today, no

part of this line remains as the tunnel was completely within the limits of the

present-day City Hall station under Broadway. The Great Blizzard of 1888 helped

demonstrate the benefits of an underground transportation system.[30] A plan

for the construction of the subway was approved in 1894, and construction began

in 1900.[31] Even though the underground portions of the subway had yet to be

built, several above-ground segments of the modern-day New York City Subway

system were already in service by then. The oldest structure still in use

opened in 1885 as part of the BMT Lexington Avenue Line in Brooklyn and is now

part of the BMT Jamaica Line. The oldest right-of-way, which is part of the BMT

West End Line near Coney Island Creek, was in use in 1864 as a steam railroad

called the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Rail Road.

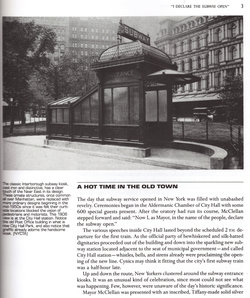

The first underground line of

the subway opened on October 27, 1904, almost 36 years after the opening of the

first elevated line in New York City (which became the IRT Ninth Avenue Line). The

9.1-mile (14.6 km) subway line, then called the "Manhattan Main

Line", ran from City Hall station northward under Lafayette Street (then

named Elm Street) and Park Avenue (then named Fourth Avenue) before turning

westward at 42nd Street. It then curved northward again at Times Square,

continuing under Broadway before terminating at 145th Street station in

Harlem.[43] Its operation was leased to the Interborough Rapid Transit Company

(IRT), and over 150,000 passengers [44] paid the 5-cent fare ($2 in 2023

dollars [45]) to ride it on the first day of operation.

By the late 1900s and early

1910s, the lines had been consolidated into two privately owned systems, the

IRT and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT, later Brooklyn–Manhattan

Transit Corporation, BMT). The city built most of the lines and leased them to

the companies.[47] The first line of the city-owned and operated Independent

Subway System (IND) opened in 1932.[48] This system was intended to compete

with the private systems and allow some of the elevated railways to be torn

down but stayed within the core of the city due to its small startup

capital.[14] This required it to be run 'at cost', necessitating fares up to

double the five-cent fare of the time, or 10¢ ($3 in 2023 dollars

In 1940, the city bought the two

private systems. Some elevated lines ceased service immediately while others

closed soon after.[50] Integration was slow, but several connections were built

between the IND and BMT. These now operate as one division, called the B

Division. Since the former IRT tunnels are narrower, have sharper curves, and

shorter station platforms, they cannot accommodate B Division cars, and the

former IRT remains its own division, the A Division.[54] Many passenger

transfers between stations of all three former companies have been created,

allowing the entire network to be treated as a single unit.

During the late 1940s, the

system recorded high ridership, and on December 23, 1946, the system-wide

record of 8,872,249 fares was set

The New York City Transit

Authority (NYCTA), a public authority presided by New York City, was created in

1953 to take over subway, bus, and streetcar operations from the city, and

placed under control of the state-level Metropolitan Transportation Authority

in 1968.

Organized in 1934 by transit

workers of the BRT, IRT, and IND,[58] the Transport Workers Union of America

Local 100 remains the largest and most influential local of the labor

unions.[59] Since the union's founding, there have been three union strikes over

contract disputes with the MTA:[60] 12 days in 1966, 11 days in 1980,[63] and

three days in 2005.

By the 1970s and 1980s, the New

York City Subway was at an all-time low. Ridership had dropped to 1910s levels,

and graffiti and crime were rampant. Maintenance was poor, and delays and track

problems were common. Still, the NYCTA managed to open six new subway stations

in the 1980s, make the current fleet of subway cars graffiti-free, as well as

order 1,775 new subway cars.[70] By the early 1990s, conditions had improved

significantly, although maintenance backlogs accumulated during those 20 years

are still being fixed today.

Entering the 21st century,

progress continued despite several disasters. The September 11 attacks resulted

in service disruptions on lines running through Lower Manhattan, particularly

the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, which ran directly underneath the World

Trade Center. Sections of the tunnel, as well as the Cortlandt Street station,

which was directly underneath the Twin Towers, were severely damaged.

Rebuilding required the suspension of service on that line south of Chambers

Street. Ten other nearby stations were closed for cleanup. By March 2002, seven

of those stations had reopened. Except for Cortlandt Street, the rest reopened

in September 2002, along with service south of Chambers Street Cortlandt Street

reopened in September 2018.

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy

flooded several underwater tunnels and other facilities near New York Harbor,

as well as trackage over Jamaica Bay. The immediate damage was fixed within six

months, but long-term resiliency and rehabilitation projects continue. The

recovery projects after the hurricane included the restoration of the new South

Ferry station from 2012 to 2017; the full closure of the Montague Street Tunnel

from 2013 to 2014; and the partial 14th Street Tunnel shutdown from 2019 to

2020.[77] Annual ridership on the New York City Subway system, which totaled

nearly 1.7 billion in 2019, declined dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic

and did not surpass one billion again until 2022.

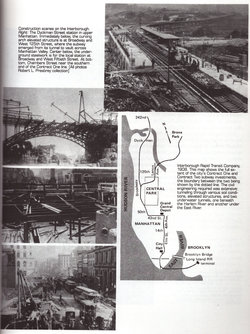

Construction methods

When the IRT subway debuted in

1904,[41] the typical tunnel construction method was cut-and-cover.[79] The

street was torn up to dig the tunnel below before being rebuilt from above.[79]

Traffic on the street above would be interrupted due to the digging up of the

street.[80] Temporary steel and wooden bridges carried surface traffic above

the construction.

Contractors in this type of

construction faced many obstacles, both natural and human-made. They had to

deal with rock formations and groundwater, which required pumps. Twelve miles

of sewers, as well as water and gas mains, electric conduits, and steam pipes

had to be rerouted. Street railways had to be torn up to allow the work. The

foundations of tall buildings often ran near the subway construction, and in

some cases needed underpinning to ensure stability.

This method worked well for

digging soft dirt and gravel near the street surface.[79] Tunnelling shields

were required for deeper sections, such as the Harlem and East River tunnels,

which used cast-iron tubes. Rock or concrete-lined tunnels were used on

segments from 33rd to 42nd streets under Park Avenue; 116th to 120th Streets

under Broadway; 145th to Dyckman Streets (Fort George) under Broadway and St.

Nicholas Avenue; and 96th Street and Broadway to Central Park North and Lenox

Avenue.

About 40% of the subway system

runs on surface or elevated tracks, including steel or cast-iron elevated

structures, concrete viaducts, embankments, open cuts and surface routes.[83]

As of 2019, there are 168 miles (270 km) of elevated tracks.[84] All of these

construction methods are completely grade-separated from road and pedestrian

crossings, and most crossings of two subway tracks are grade-separated with

flying junctions. The sole exceptions of at-grade junctions of two lines in

regular service are the 142nd Street and Myrtle Avenue junctions, whose tracks

intersect at the same level, as well as the same-direction pairs of tracks on

the IRT Eastern Parkway Line at Rogers Junction.

The 7,700 workers who built the

original subway lines were mostly immigrants living in Manhattan.

More recent projects use tunnel

boring machines, which increase the cost. However, they minimize disruption at

street level and avoid already existing utilities.[89] Examples of such

projects include the extension of the IRT Flushing Line and the IND Second

Avenue Line.

Expansion

Since the opening of the

original New York City Subway line in 1904,[41] multiple official and planning

agencies have proposed numerous extensions to the subway system. One of the

more expansive proposals was the "IND Second System", part of a plan

to construct new subway lines in addition to taking over existing subway lines

and railroad rights-of-way. The most grandiose IND Second Subway plan,

conceived in 1929, was to be part of the city-operated IND, and was to comprise

almost 1⁄3 of the current subway system.[97][98] By 1939, with unification

planned, all three systems were included within the plan, which was ultimately

never carried out.[99][100] Many different plans were proposed over the years

of the subway's existence, but expansion of the subway system mostly stopped

during World War II.

Though most of the routes

proposed over the decades have never seen construction, discussion remains

strong to develop some of these lines, to alleviate existing subway capacity

constraints and overcrowding, the most notable being the proposals for the Second

Avenue Subway. Plans for new lines date back to the early 1910s, and expansion

plans have been proposed during many years of the system's existence.

After the IND Sixth Avenue Line

was completed in 1940, the city went into great debt, and only 33 new stations

have been added to the system since, nineteen of which were part of defunct

railways that already existed. Five stations were on the abandoned New York,

Westchester and Boston Railway, which was incorporated into the system in 1941

as the IRT Dyre Avenue Line.[103] Fourteen more stations were on the abandoned

LIRR Rockaway Beach Branch (now the IND Rockaway Line), which opened in

1955.[104] Two stations (57th Street and Grand Street) were part of the Chrystie

Street Connection, and opened in 1968; the Harlem–148th Street terminal opened

that same year in an unrelated project.

Six were built as part of a 1968

plan: three on the Archer Avenue Lines, opened in 1988,[108] and three on the

63rd Street Lines, opened in 1989.[109] The new South Ferry station was built

and connected to the existing Whitehall Street–South Ferry station in

2009.[110] The one-stop 7 Subway Extension to the west side of Manhattan,

consisting of the 34th Street–Hudson Yards station, was opened in 2015, and

three stations on the Second Avenue Subway in the Upper East Side were opened

as part of Phase 1 of the line at the beginning of 2017.

Lines and routes

Many rapid transit systems run

relatively static routings, so that a train "line" is more or less

synonymous with a train "route". In New York City, routings change

often, for various reasons. Within the nomenclature of the subway, the

"line" describes the physical railroad track or series of tracks that

a train "route" uses on its way from one terminal to another.

"Routes" (also called "services") are distinguished by a

letter or a number and "lines" have names. Trains display their route

designation.

There are 28 train services in

the subway system, including three short shuttles. Each route has a color and a

local or express designation representing the Manhattan trunk line of the

service.New York City residents seldom refer to services by color (e.g.,

"blue line" or "green line") but out-of-towners and

tourists often do.

The 1, C, G, L, M, R, and W

trains are fully local and make all stops. The 2, 3, 4, 5, A, B, D, E, F, N,

and Q trains have portions of express and local service. J, Z, 6, and 7 trains

vary by direction, day, or time of day. The letter S is used for three shuttle

services: Franklin Avenue Shuttle, Rockaway Park Shuttle, and 42nd Street

Shuttle.

Though the subway system

operates on a 24-hour basis, during late night hours some of the designated

routes do not run, run as a shorter route (often referred to as the

"shuttle train" version of its full-length counterpart) or run with a

different stopping pattern. These are usually indicated by smaller, secondary

route signage on station platforms. Because there is no nightly system shutdown

for maintenance, tracks and stations must be maintained while the system is

operating. This work sometimes necessitates service changes during midday,

overnight hours, and weekends.

Out of the 472 stations, 467 are

served 24 hours a day.[note 9] Underground stations in the New York City Subway

are typically accessed by staircases going down from street level. Many of

these staircases are painted in a common shade of green, with slight or

significant variations in design.[147] Other stations have unique entrances

reflective of their location or date of construction. Several station entrance

stairs, for example, are built into adjacent buildings. Nearly all station

entrances feature color-coded globe or square lamps signifying their status as

an entrance. The current number of stations is smaller than the peak of the

system. In addition to the demolition of former elevated lines, which

collectively have resulted in the demolition of over a hundred stations, other

closed stations and unused portions of existing stations remain in parts of the

system.

Many stations in the subway

system have mezzanines. Mezzanines allow for passengers to enter from multiple

locations at an intersection and proceed to the correct platform without having

to cross the street before entering. Inside mezzanines are fare control areas,

where passengers physically pay their fare to enter the subway system. In many

older stations, the fare control area is at platform level with no mezzanine

crossovers. Many elevated stations also have platform-level fare control with

no common station house between directions of service.

Upon entering a station,

passengers may use station booths (formerly known as token booths)[153] or

vending machines to buy their fare, which is currently stored in a MetroCard.

Each station has at least one booth, typically located at the busiest entrance.[154]

After swiping the card at a turnstile, customers enter the fare-controlled area

of the station and continue to the platforms. Inside fare control are

"Off-Hours Waiting Areas", which consist of benches and are

identified by a yellow sign.

Platforms

A typical subway station has

waiting platforms ranging from 480 to 600 feet (150 to 180 m) long. Some are

longer. Platforms of former commuter rail stations—such as those on the IND

Rockaway Line, are even longer. With the many different lines in the system,

one platform often serves more than one service. Passengers need to look at the

overhead signs to see which trains stop there and when, and at the arriving

train to identify it.

There are several common

platform configurations. On a double track line, a station may have one center

island platform used for trains in both directions, or two side platforms, one

for each direction. For lines with three or four tracks with express service,

local stops will have side platforms and the middle one or two tracks will not

stop at the station. On these lines, express stations typically have two island

platforms, one for each direction. Each island platform provides a

cross-platform interchange between local and express services. Some four-track

lines with express service have two tracks each on two levels and use both

island and side platforms